The Reshaping of the Terrorist and Extremist Landscape in a Post Pandemic World

A major research program investigating the impact of COVID-19 on terrorist and extremist narratives.

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia was particularly proactive with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Although caseloads worsened the following year, pandemic-related health measures restricted regional mobility in general and violent extremist activity in particular. Pro-Daesh activity was substantially reduced until an uptick in late '21.

Choose which year of analysis to view via the slider below: 2021 or 2020.

Regional Summary | Choose Year

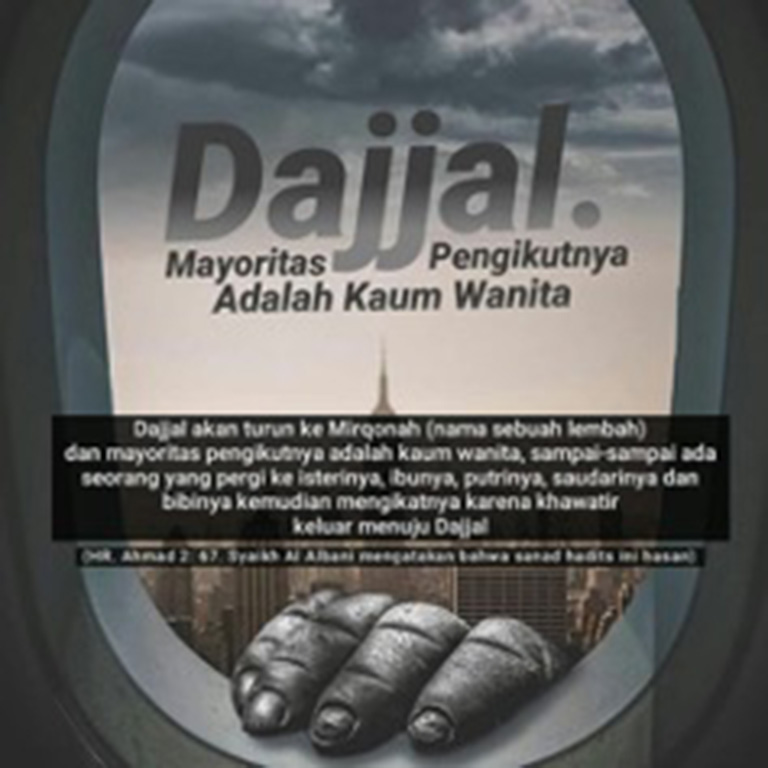

Violent Extremist Organizations (VEOs) and Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs) across Southeast Asia appeared to adopt a wait-and-watch approach to the new conditions, many of them turning inward, retreating into apocalyptic visions inspired by the unfolding global pandemic. Violent attacks were deprioritized and, in any case, were difficult to conduct in Indonesia, given effective counter-terrorism policing.

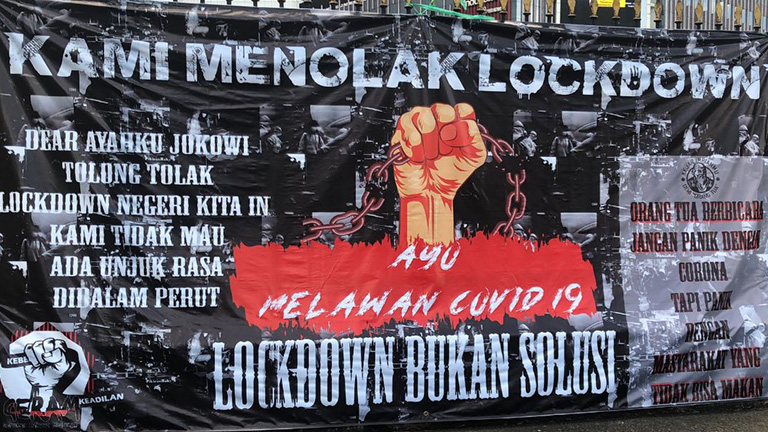

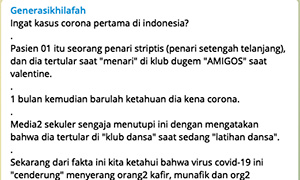

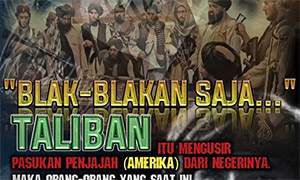

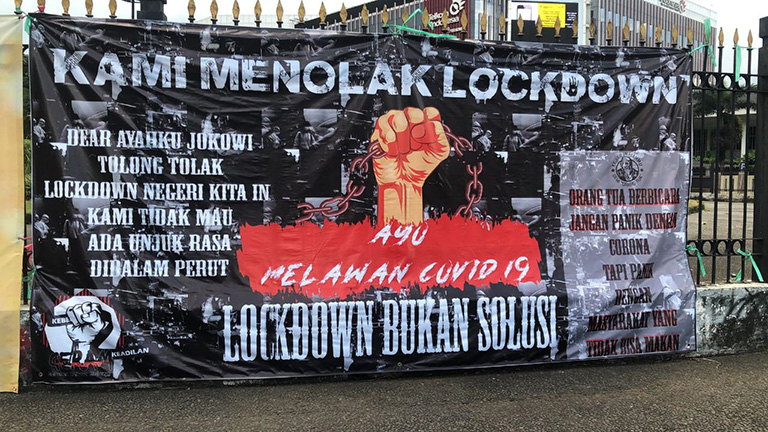

The pandemic’s impact on the People’s Republic of China and then the West was watched with glee by many groups, who interpreted the virus as divine retribution against the enemies of Islam. Over time, and as lockdowns and other pandemic interventions were rolled out, most VEOs adopted conspiratorial narratives that understood the pandemic as a hidden plot by powerful Western or Chinese interests. In adopting such narratives, actors disseminated anti-vaccination and related disinformation, much of it adapted from Western, especially US, sources.

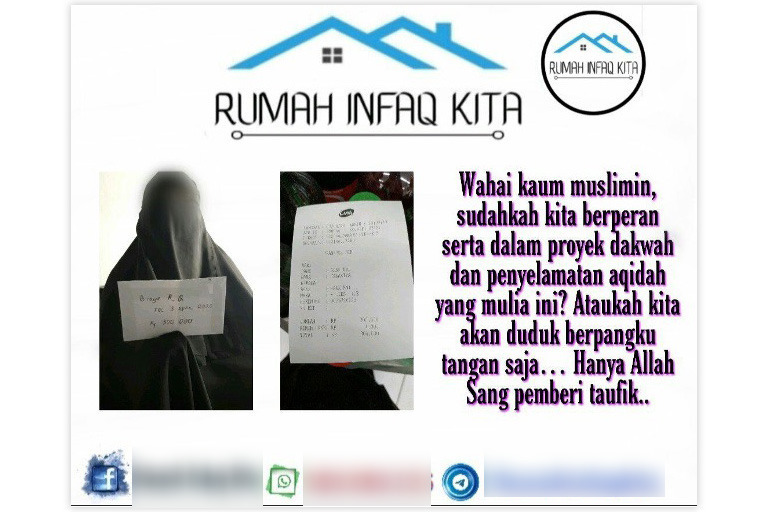

Examples of extremist narratives and propoganda from South East Asia

Support for Daesh in its two major regional hotspots of the Republic of Indonesia and the Republic of the Philippines declined, in line with the decline of Daesh in the Middle East, partially due to the restrictions on mobility, but also due to counter-terrorism efforts that had been in effect since before the virus outbreak. In Indonesia, the Government continued to press their advantage against the Islamist opposition, and the capabilities of counter-terrorism police were at their peak.

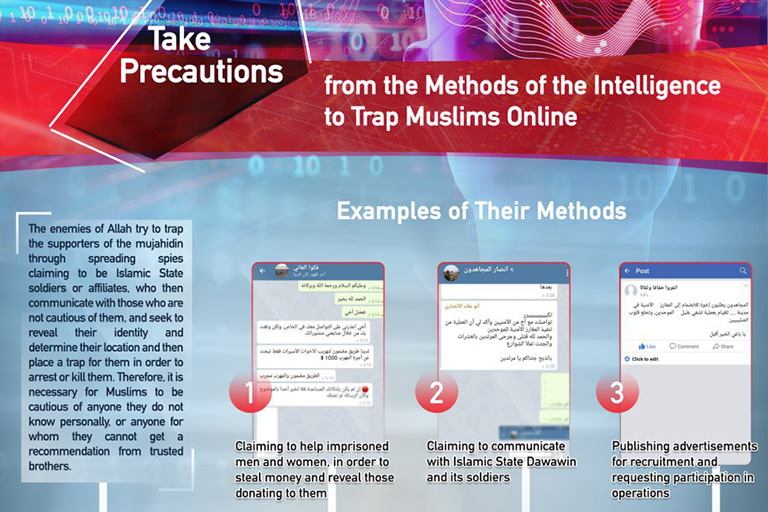

Local Daesh affiliates, known as Jamaah Anshorut Daulah (JAD), were reduced to scatterings of small, largely autonomous cells. Large-scale shutdowns by the Telegram platform to remove violent extremist content restricted Daesh sympathizers to small chat groups with limited lifespans of 100-200 subscribers. In the Philippines, the relative success of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) under the auspices of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) limited the opportunities for splintering into militant offshoots, such as those that coalesced in 2017 under the banner of Daesh in the siege of Marawi city.

Generally, the pandemic reduced VE activity across Southeast Asia. The most notable example of this effect was the unprecedented unilateral ceasefire declared in April 2020 by the National Revolutionary Front (BRN), the largest armed group in the 16-year Malay- Muslim insurgency in southern Thailand. The BRN entered a peace dialogue with the Thai government, facilitated by the Federation of Malaysia. But as the pandemic dragged on, peace began to fray, and sporadic attacks occurred. For the region as a whole, the post- pandemic period will likely see a rebound in VE activity as travel and crowds return to their pre-pandemic levels.

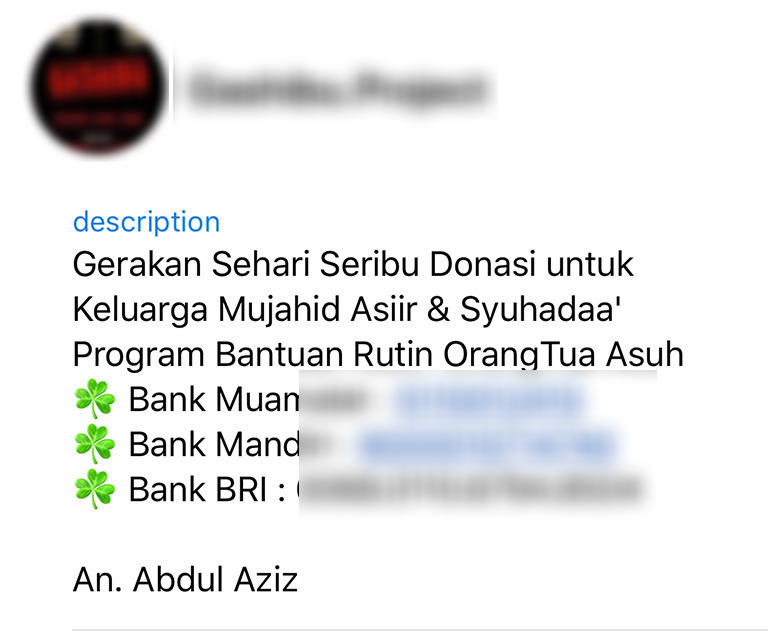

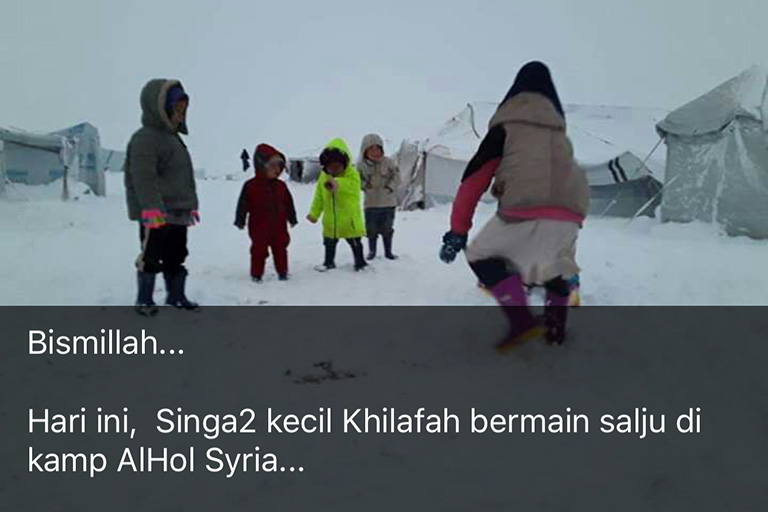

A pro-Daesh charity outreach post from Indonesia featured on social media during mid-2020. Source: Telegram.

The pandemic accelerated trends in online radicalization and recruitment as the internet continues to displace face-to-face networking. Regional violent extremist activity— already heterogeneous and marked by a disparate constellation of VEOs—became ever more insular and localized, as militants focused on the welfare of their communities via an expanding network of charities or contemplated and prayed for the end times.

One of the lasting marks of the period of pandemic isolation may be the growth of extremist- linked charities and foundations, especially in Indonesia, against the backdrop of the flourishing of mainstream charities in Indonesia during this period.

Although violent extremist activity was at a low ebb by the end of 2020, there are indications that the pandemic period may represent a temporary lull. Foreign fighters and their families could find their way back to the region as mobility restrictions are eased and travel routes reopen.

But for now, the pandemic drags on across Southeast Asia, with some predicting effects running through 2024-2025. The course of violent extremism is always hard to anticipate in a region so diverse, and even broad trends can be challenging to identify. When it finally arrives, the post-pandemic period will likely reveal a changed Southeast Asia in many respects, and the landscape of terrorism and violent extremism will be no exception.

Policy Recommendations

- Continue to analyze militant narratives and operational structures in anticipation of a return to the status quo ante, especially once regional and international travel is restored. Although violent extremist activity has decreased during the pandemic period in Southeast Asia, there is a likelihood of a rebound in activity post-pandemic.

- Governments and civil society organizations (CSO) should provide services to children and families of fighters to supplant Daesh charities and enhance disengagement from violent extremism. Charities are the one area in which violent extremist-linked activity remains undiminished by the pandemic. Pro-Daesh foundations are both an indicator of a gap in government service provision and a risk of future re-engagement in terrorism. Greater public awareness of the need for due diligence when donating to charities might reduce the risk of unintentional funding of VE-linked groups.

- Social media platforms and educational institutions should counter and disrupt propaganda from VEOs using anti-Chinese conspiracy theories as a mobilizing narrative. Anti-Chinese sentiment, exacerbated by the pandemic, presents a risk of communal conflict targeting ethnic Chinese and, as an issue that appeals to prejudices across the region, may serve as a cause that unifies otherwise disparate VEOs.

- COVID-19 misinformation and disinformation became endemic in violent extremist communication channels by the close of 2020. This misinformation takes the form of narratives that appeal to the full spectrum of violent extremist actors in Southeast Asia. Yet, at the outset of the year, pandemic content on VE communication channels was more consistent with sound public health advice. A solution may be to deliver public health messages to VE channels via credible third parties, such as CSOs and trusted religious actors rather than national governments distrusted by violent extremist actors.

Footnotes

Thomas Hale, Noam Angrist, Rafael Goldszmidt, Beatriz Kira, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips, Samuel Webster, Emily Cameron-Blake, Laura Hallas, Saptarshi Majumdar, and Helen Tatlow. (2021). “A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker).” Nature Human Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8, as used by Our World In Data; and, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), acleddata.com.

Visit SourceCOVID-19 data aggregated from Our World in Data (https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases) based on confirmed cases sourced from the COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science (https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19) and Engineering (CSSE)) at Johns Hopkins University; and, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED, acleddata.com).

Region reports

For full analysis and recommendations, download the region reports for 2020 and 2021.