The Reshaping of the Terrorist and Extremist Landscape in a Post Pandemic World

A major research program investigating the impact of COVID-19 on terrorist and extremist narratives.

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia was particularly proactive with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Although caseloads worsened the following year, pandemic-related health measures restricted regional mobility in general and violent extremist activity in particular. Pro-Daesh activity, especially, was substantially reduced until an uptick in late '21.

Choose which year of analysis to view via the slider below: 2021 or 2020.

Region Summary | Choose Year

In 2021, violent extremist activity in Southeast Asia showed signs of returning to pre-pandemic levels as countries eased COVID-19 restrictions, while regional cases of the virus reached their highest levels by the third quarter of the year. At the same time, according to a report from the Singapore-based International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR), the overall number of terrorist incidents in Southeast Asia declined in 2021.1 Nevertheless, Al-Qaeda and Daesh-aligned militants demonstrated a capacity to conduct sporadic high-impact attacks, primarily in Indonesia and the Philippines. These two countries have been the most vulnerable to the spread and threat of violent extremism and terrorism.

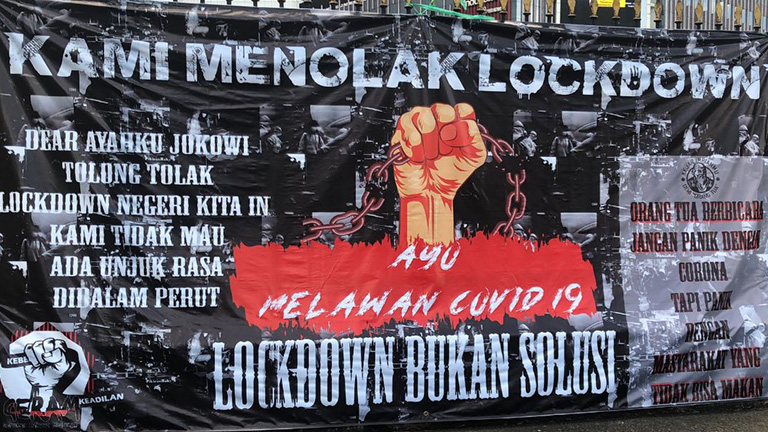

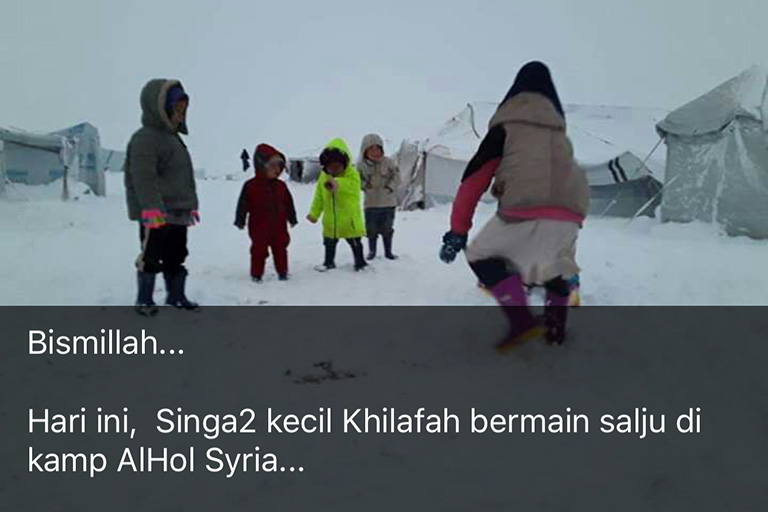

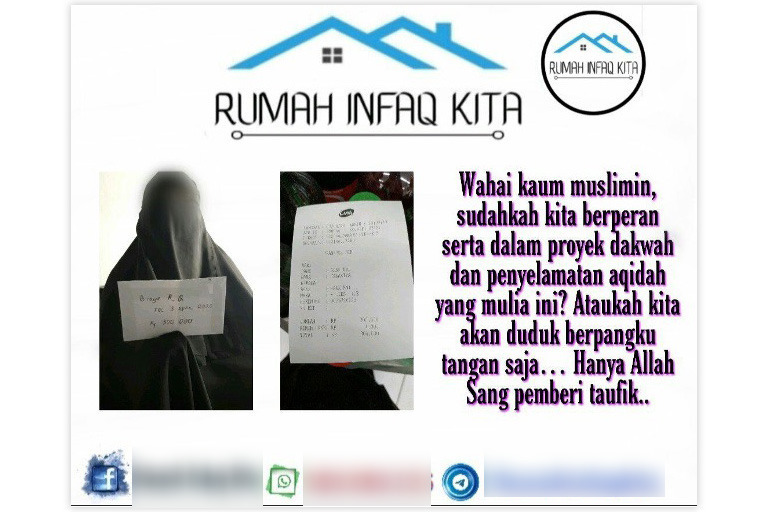

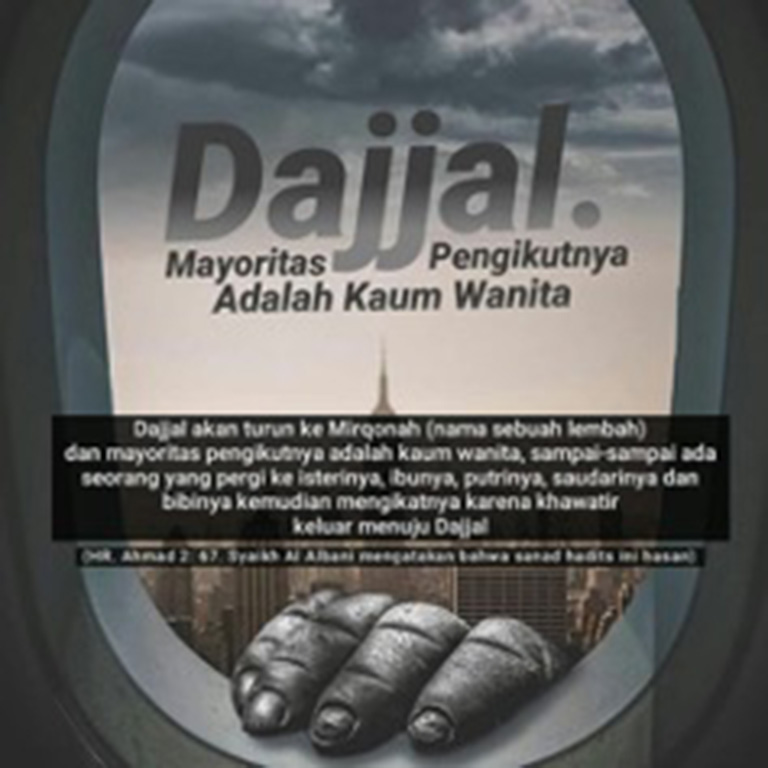

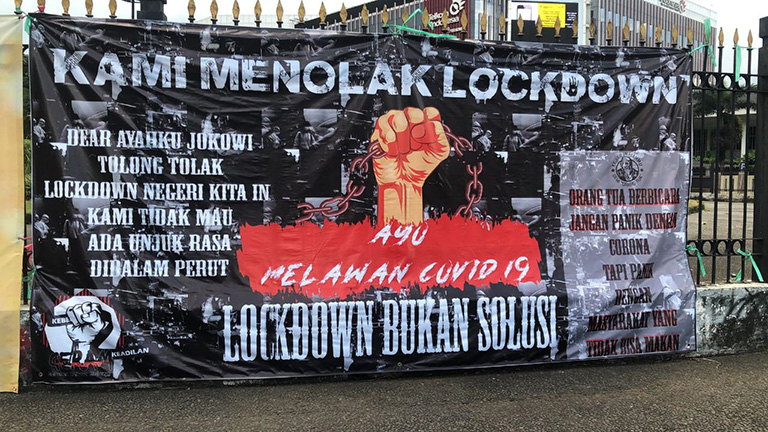

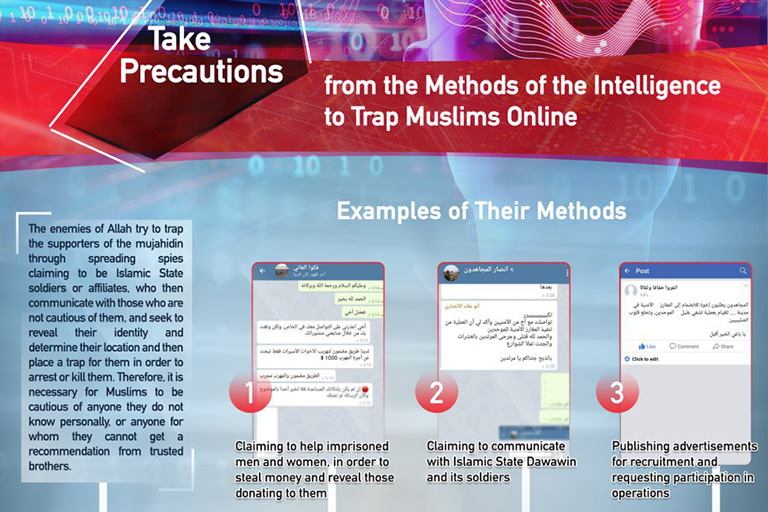

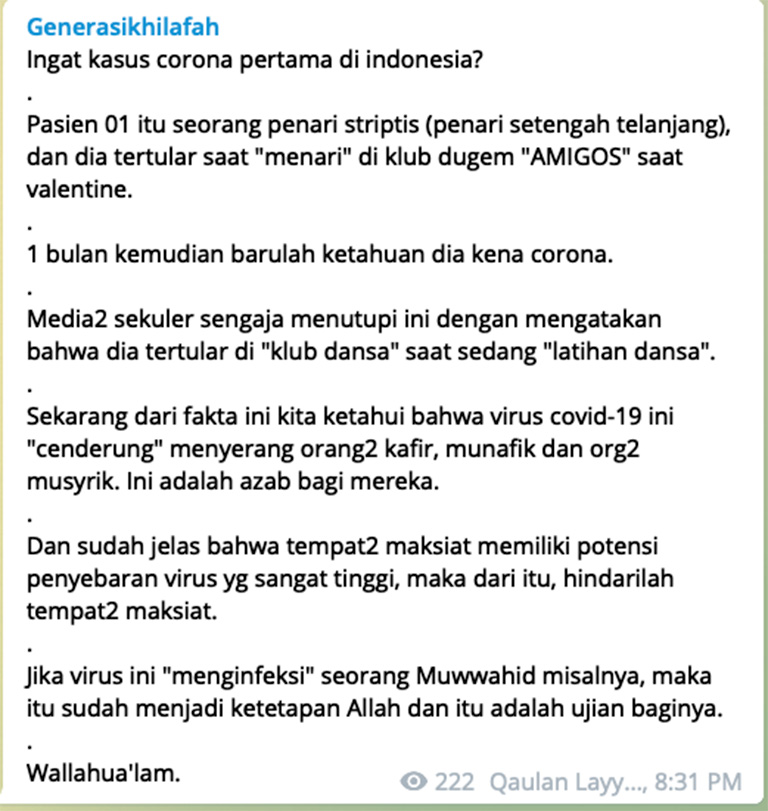

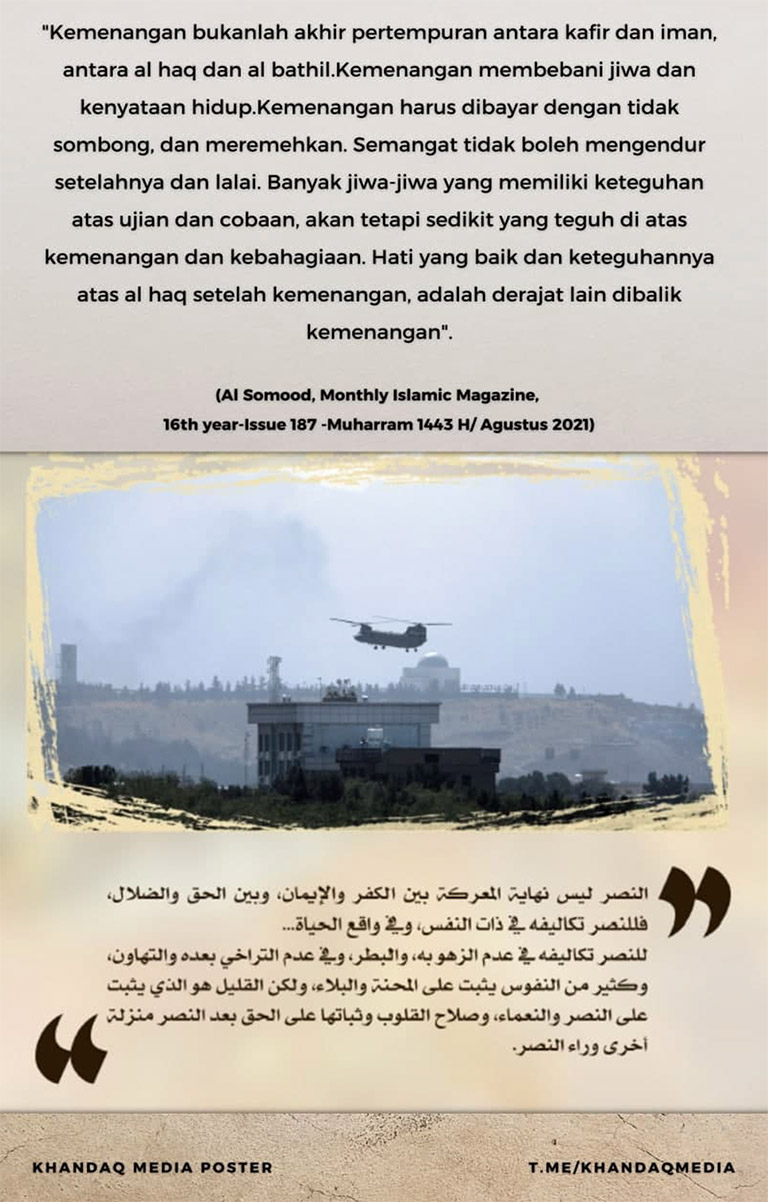

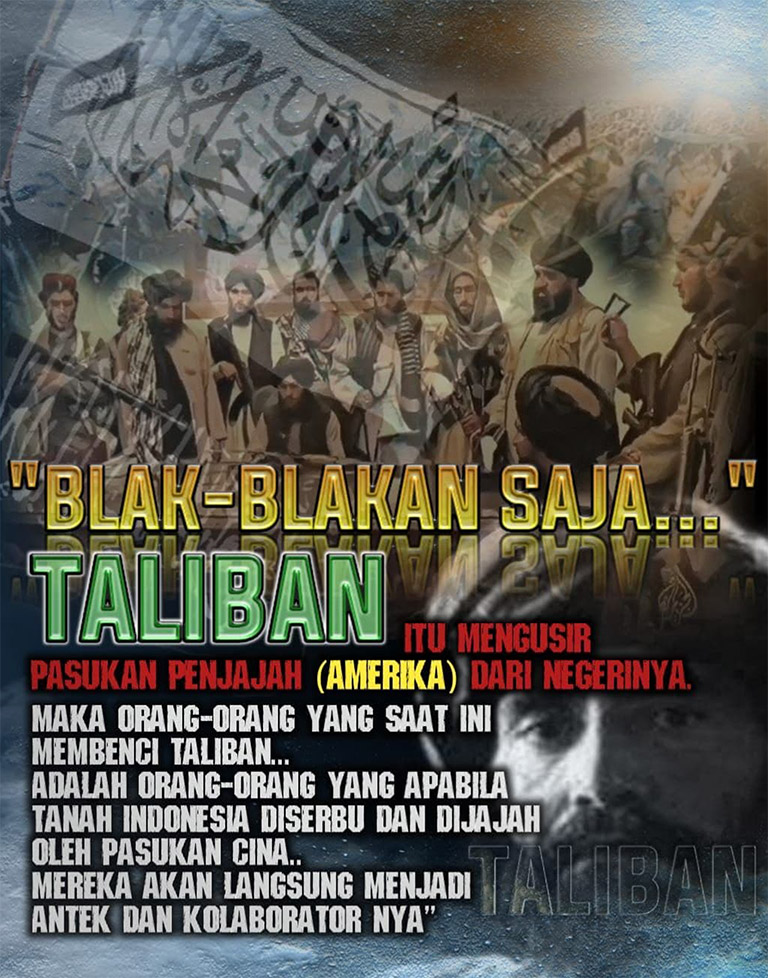

Examples of extremist narratives and propoganda from South East Asia

In March 2021, Daesh followers attacked the Jakarta police headquarters and a church in Eastern Indonesia. Multiple arrests in this country revealed that the al-Qaeda-aligned Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) group has a considerably more significant presence than previously thought.2 JI is limited to Indonesia and has nowhere near the strength displayed in the early 2000s when the group represented a Southeast Asian regional network with strong ties to Al-Qaeda. There is a risk that the group’s recent rise prefigured the region’s return to pre-Daesh patterns when JI was the dominant, violent extremist network capable of linking militants in Southeast Asia to battle zones across the world, notably in Afghanistan.3 The developments and the deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan compound this risk over the longer term.

Similar ideologies and subscribers were also responsible for attacks in the Philippines across 2021. The pro-Daesh Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), for instance, attacked villages on mainland Mindanao in the same month, displacing thousands of civilians.4 These assaults led the towns of Datu Saudi Ampatuan, Shariff Saydona Mustapha, and Mamasapano to declare “a state of calamity.”5

Despite a return to prominence in 2021, Daesh is organizationally weak in the two areas in the region where it has previously been the strongest: Central Sulawesi (Indonesia) and Mindanao (Southern Philippines). Pro-Daesh insurgents in Central Sulawesi acting under the banner of the East Indonesia Mujahidin (MIT: Mujahidin Indonesia Timor) are nearing a total military defeat following the killing of the group’s leader, Ali Kalora, in a shootout in September 2021.6 In Mindanao, Abu Sayyaf Group militants responsible for the spate of suicide bombings in the Sulu archipelago have been killed or kept constantly on the run by the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). BIFF fighters in central Mindanao are increasingly isolated as their former allies, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), cooperates with Manila in the ongoing peace process.7

Counter-terrorism operations across the Philippines and Indonesia have greatly restricted the physical space in which militants can operate. Consequently, Daesh no longer has a safe haven in Southeast Asia and it has no clear leader (emir) after the death of Salahuddin Hassan in a military raid in the Southern Philippines in October 2021.8 The restriction of extremists’ and militants’ ability to act offline alongside the growing role of the internet in radicalization and recruitment suggests that the intensive exploitation of cyberspace may be one of the legacies of the pandemic in Southeast Asia. In 2021, in online forums such as Telegram, militants from across the spectrum gathered and interacted in new ways as they continued to play a cat-and-mouse game with cyber authorities and platform moderators. Meanwhile, overall COVID-19 related narratives from extremist organizations seemed to decline in favor of continued anti-governmental propaganda and exaggerated territorial claims from Daesh-affiliates. Online militants – even Daesh sympathizers – were also energized by the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan and the rapid collapse of the previously democratically elected government in August 2021.9

Adapting to online content removal and monitoring efforts by tech platforms, primary data analysis by the authors reveals that pro-Daesh actors in Southeast Asia are leading a shift to decentralized social media technologies to avoid bans and content moderation takedowns.10 The intensified scrutiny of online content by governments has been prompted in part by increased online socialization during the pandemic period, as spoken to in detail throughout the 2020 iteration of this report. This trend dovetails with the increased popularity of more decentralized and encrypted online platforms and technologies – Telegram, Matrix, and Element, for example – that may shift the balance of online power and content access potentially away from large platforms to more distributed, acephalous platforms. The combined presence of these, largely decentralized platforms increasingly based on blockchain technologies is referenced across this report. However, it remains to be observed to what extent Daesh activists and extremists more generally can convert their online capabilities into offline action and how effective their growing use of non-mainstream social media platforms will truly be.

While the pandemic drags on, as indicated by resurgent caseloads towards the end of 2021 in Thailand, Indonesia, and elsewhere in SE Asia, violent extremism in the region is unlikely to reach pre-pandemic levels. However, as COVID-19 restrictions on travel and events ease and governments shift to policies of “living with the virus,” it is likely that extremism in the region will return to the norm over the long term. Violent extremism may rebound as militants see opportunities to disrupt upcoming election cycles in key countries, first in presidential and central government elections in the Philippines in 2022 and later in the 2024 national elections in Indonesia.

Policy Recommendations

- Authorities should prepare for a potential rebound in violent extremist activity, with national election cycles approaching in the Philippines in 2022 and Indonesia in 2024, COVID-19 restrictions easing, and inter-and intra-regional travel on the rise. This will be a shift from the more conducive environment during the pandemic for counter-terrorism authorities across Southeast Asia, which saw a decline in violent incidents, a ceasefire in Southern Thailand, and successful counter-terrorism operations in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

- P/CVE practitioners and government should increase online countermeasures such as positive interventions and ‘pre-bunking’ narratives via inoculation theory techniques to prevent battlefield propaganda from Afghanistan from proliferating further and inspiring offline operations in Southeast Asia. The Taliban’s return to power and the intensified fighting between Taliban forces and Daesh (IS-Khorasan) in Afghanistan have given inspiration to all sides of the extremist community in Southeast Asia.

- Social media platforms must adapt their systems to detect more nuanced forms of messaging – and those offered in local languages – than current algorithms are able to capture. Platforms should also collaborate more closely with localized subject-matter experts to bolster their knowledge of and capacity to detect signals and language patterns being used by terrorist groups. Mainstream and especially less popular social media platforms remain vulnerable to violent extremist actors, despite the advances made in recent years in automatic detection and content moderation. The Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT), Tech Against Terrorism (TaT), and the Extremism and Gaming Research Network (EGRN) all offer complementary and accessible resources for platforms and regulators alike to improve their efforts in the P/CVE space.

- Authorities and policymakers are encouraged to develop new tools and methods to counter extremist content and novel disinformation tools as the transition to decentralized communications and social media technology begins to impact Southeast Asia. Although decentralized communications are at an embryonic stage, the region hosts a tech-savvy population who are likely to be early adopters of such technologies, potentially making it easier for extremists to radicalize, propagandize, and recruit on alternative platforms.

- Authorities are advised to prepare for a possible post-pandemic scenario in which JI emerges as the strongest violent extremist network in the region. Arrests of networks of JI militants in Indonesia indicate that the organization is much larger and more structured than assumed. In recent years, JI has succeeded in raising donations and capital as part of a move into above-ground business operations. Although JI has pursued a strategy of avoiding conflict to date, more violent and less patient JI splinter groups, facilitated by sophisticated cyber technologies, should be anticipated.

Footnotes

International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR), “Counter Terrorism Trends and Analysis,” RSIS, January 2022

Visit Source“Police Arrest 13 Suspected Jemaah Islamiyah in Sumatra,” Jakarta Globe, December 17, 2021

Visit SourceCharles Vallee, “Jemaah Islamiyah: Another Manifestation of al Qaeda Core's Global Strategy,” Centre for Strategic and International Studies, March 22, 2018

Visit Source“3 Maguindanao towns declare state of calamity over skirmishes,” Philippine News Agency, April 2, 2021

Visit SourceIbid.

“Menumpas Jaringan Terorisme,” Media Indonesia, September 20, 2021

Visit Source“The Philippines: Extremism and Terrorism,” Counter Extremism Project, 2022

Visit Source“Philippine Govt Forces Kill Top IS Militant, Wife in Mindanao Raid,” Benar News, October 29, 2021

Visit SourceNote: Based on primary source analysis of an internal Telegram dataset referred to elsewhere in this report as “ARK Telegram Data, 2020-2021.”

Ibid.

Region reports

For full analysis and recommendations, download the region reports for 2020 and 2021.