The Reshaping of the Terrorist and Extremist Landscape in a Post Pandemic World

A major research program investigating the impact of COVID-19 on terrorist and extremist narratives.

About the program

This report series by Hedayah reflects on and analyzes over two years of global changes in violent extremism (VE) and terrorism wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

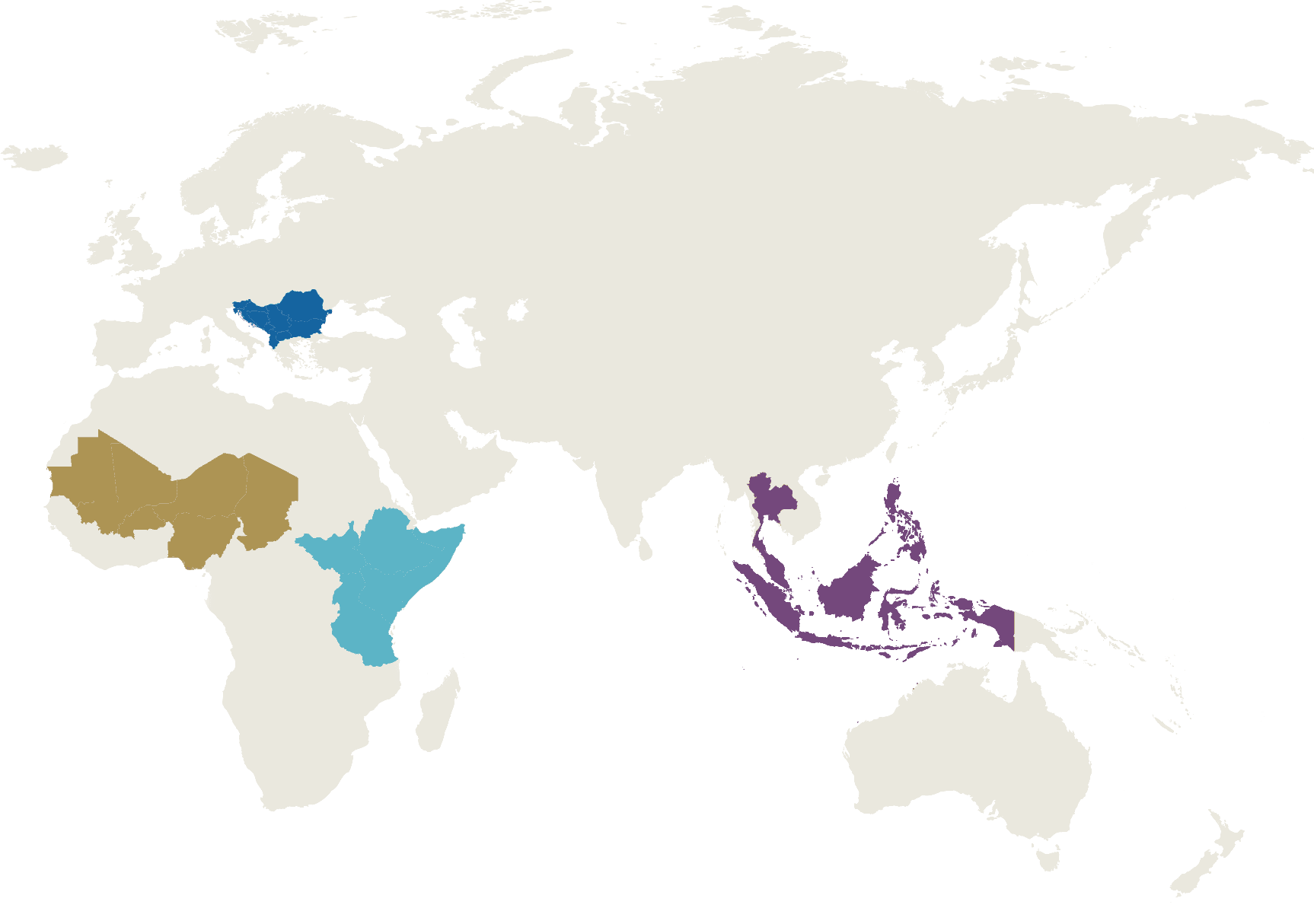

The report series prioritizes examining extremist narratives and related activities across four regions, each chosen for the presence of active violent extremist organizations (VEOs) and a paucity of relevant existing research at the time of project design.

The following insights across this site synthesize primary and secondary data from research teams comprised of experts from designated regions of focus: the Balkans, East Africa, West Africa, and Southeast Asia. Annual reports for 2020 and 2021 offer further in-depth research into narratives, trends, and policy recommendations. For readers seeking additional detail, downloadable regional reports (in PDF) are available for 2020 and 2021.

Geographic Coverage

COVID-19 has influenced radicalization and violent extremism patterns differently across the world. Over 2020 and most of 2021, the years analyzed for this study, public health measures and restrictions limited the capabilities of many violent extremist organizations to conduct activities on the ground, namely to recruit, organize mass audience activities, or carry out attacks as readily. With variations across regions, foreign terrorist fighters generally found their movements restricted and reduced by closed borders. However, as restrictions eased in 2021, violent extremist activities and terrorist attacks gradually escalated once again. This trend will likely continue amid returns to normal.

Despite that rebound, reductions in violent extremist activity were particularly notable in Southeast Asia – in no small part due to changes in governmental policy and renewed enforcement activities. Conversely, in West Africa, violent extremist activity increased in both years, taking advantage of the impacts of the pandemic on overburdened governments while manipulating public health backlash to their advantage. Country-level dynamics in East Africa led to increased violence in Somalia and the provision of limited public health services by Al-Shabaab, along with an increase year on year in observable violent extremism in Kenya and Ethiopia. Uganda also experienced a spike in terrorist attacks towards the end of 2021. In the Balkans, the foremost preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE) concern was the rise of the radical right, often enmeshed within conspiracy theories and fueled by harmful online narratives and ethnonationalist ideologies.

Ideologically motivated extremist groups quickly revised their narratives to address COVID-19. Capitalizing on the pandemic, VEOs opportunistically sought to influence and mobilize new followers through novel fears while justifying their broader ideologies, often already including anti-government, anti-Western, anti-Chinese, and ethnonationalist aims. While specific narratives used varied significantly, several common themes in metanarratives emerged, including:

- Restrictions as Repression – a propagandized view that government pandemic measures were unjust, disproportionate, or designed only to control specific groups of people;

- Divine Retribution –promoting that COVID-19 was a form of punishment from God or was a “soldier of Allah” that would only attack enemies of religion;

- Weaponized Conspiracies – explanations of COVID-19 and vaccines fueled by widespread mis- and disinformation used to bolster extremist credibility;

- End Times – a metanarrative holding that the pandemic was a sign of an apocalyptic end of the world, often coupled with the belief that devout followers of specific ideologies advanced by extremists would be saved;

- Intensified Ethnonationalism – extremist narratives primarily across the Balkans pairing COVID-19 grievances with radical right and ethnonationalist ideologies; and,

- Foreign Fighter Plight – narratives based on the cultivation of solidarity between lay followers and foreign terrorist fighter families perceived to be persecuted or particularly suffering during the pandemic.

Repressive restrictions, divine retribution, and weaponized conspiracy metanarratives were particularly prevalent and influential throughout all four regions: these are addressed in-depth though the links below.

2021 marked a shift in the use of weaponized conspiracy theories by extremist groups. In SE Asia and West Africa, amid loosening public health restrictions and less compliance with those remaining, extremists’ use of COVID-19 related narratives broadly diminished. In the Balkans, however, extremist-related groups stepped up their use of weaponized narratives. No longer focused on denying the existence of the pandemic, conspiracies about the vaccine blurred with antisemitic, anti-democratic, and nativist rhetoric spread by ideologically motivated actors, mainly on the radical right. Meanwhile, in East Africa, Al-Shabaab weighed in on which vaccines were acceptable, inveighing against AstraZeneca and promoting its own, religiously-based remedies. Given the limited rollout and persistent vaccine inequality across the African continent, and as vaccination campaigns hopefully increase in 2022, extremist rhetoric will probably increasingly tap into conspiracies around the vaccines. Evidence from other regions and limited cases across the continent in 2021 indicate that extremist groups may cast them as weapons of the “West,” un-Islamic (haram), or as bioweapons designed to attack specific ethnicities.

Interestingly, select narratives have been repurposed among ideologically opposed violent extremist actors. Extremist narratives were duplicated and adapted between non-aligned groups across the world, frequently drawing on transnational misinformation or Western radical right propaganda, including anti-vaccine and anti-globalism tropes. This incongruous ‘ideological buffet’ has cross-pollinated conspiracy theories and metanarratives between seemingly divergent groups across the ideological spectrum. Common enemies and fears – globalism, vaccine companies, public health workers – may result and increasingly become the norm.

Extremist groups also hastened their shift from in-person to online radicalization and recruitment. Although this transition has been years in the making, the pandemic intensified online dissemination of extremist propaganda and virtual activities on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and WhatsApp. Audio clips of sermons, the novel use of time-bound Instagram stories in attempts to dodge moderation, and strategic memetic (the use of memes) propaganda warfare proliferated. Groups also increased their use of newer, encryption-capable platforms: Telegram groups featured in all regions despite stepped-up content takedowns of Daesh-linked content. International police and Indonesian governmental crackdowns on Telegram groups shut down large VEO groups, but smaller cells remained. Meanwhile, Gab, VK, and TamTam all emerged as platforms of importance in the Balkans. In 2021, pro-Daesh groups in SE Asia experimented with novel, decentralized communication platforms, including Matrix and Element, while working on propaganda distribution platforms such as Jihadflix.

An adaptation to virtualized communications reflected an operational necessity for groups dependent on physical contact as they became restricted by public health orders. But it also provided an opportunity to reach a more expansive, captive audience: lockdowns and reduced offline interactions led to a global surge in screen time in 2020 and 2021. While organizations globally have struggled to shift operations online, VEOs have often been ahead of the curve while rapidly upgrading their online capacities. The continued use of new platforms in 2021, even as life returned to public socialization in most of the world, demonstrates this reality.

With wide variations across firms, social media platforms broadly sought to limit violent extremist content and COVID-19 mis- and disinformation. Following government orders and internal trust and safety policy efforts, platforms, especially members of the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT), underwent large-scale removals of extremist content. These limitations encouraged VEOs to use other, smaller platforms or adapt their use of social media features. In Southeast Asia, Daesh affiliates used “Instagram Story” functions in an attempt to dodge content flagging by displaying it for only 24 hours before automatically disappearing. In West Africa and the Balkans, groups spread their content via encrypted messaging apps like WhatsApp, Viber, TamTam, and, if properly configured, Telegram. VEOs in East Africa relied predominantly on mainstream social media platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, to spread targeted narratives – potentially reflecting a lack of content moderation and trust and safety capacities in local languages. In the Balkans, radical right conspiracy narratives and disinformation campaigns often featured in mainstream media and politics, providing contextual cover from moderation efforts. Even as platforms and policy actors adapt, VEOs and extremist groups will continue to circumvent moderation efforts by finding new and smaller platforms to spread rhetoric and communicate among their members. This balloon effect, shifting content from one platform to another after enforcement actions, shows no sign of abating, nor do continued attempts by extremist entities to use large platforms and reach wider audiences despite improved moderation work.

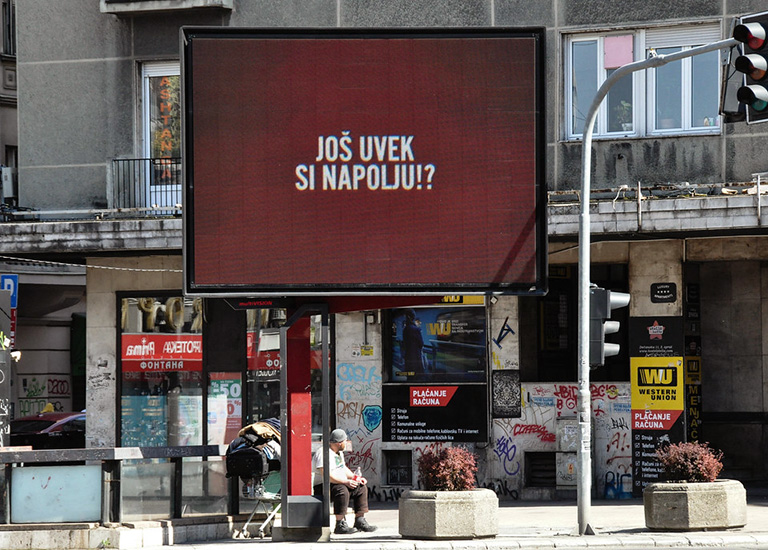

Although diminished in some countries, offline radicalization and recruitment efforts during the pandemic remained a significant P/CVE challenge. For instance, VEOs in West Africa continued to use traditional preaching and Friday prayers to disseminate COVID-19 narratives and ideological messages. In the Balkans, radical right groups and conspiracy theorists attended anti-government protests to leverage public anger toward their ideological ends. In under governed spaces, VEOs entrenched themselves more deeply in communities. For instance, Al-Shabaab in Somalia actively provisioned public health services, while pro-Daesh charities and foundations in Southeast Asia flourished by directly assisting communities in need due to the pandemic.

While varied country-to-country, P/CVE efforts were often constrained by the unfolding pandemic with resources and attention focused on the COVID-19 response. As extremist groups weaponized mis- and disinformation about the pandemic to their own ends, scattershot public policy responses to these narratives risks a long-term detrimental impact on P/CVE and public health efforts. Their corrosive impact on trust, especially towards health and security actors, will not disappear soon. Still, the global picture provides nuance. In countries like Indonesia, governments used public health responses while also availing themselves of a policy window created by the pandemic to increase policing against violent extremism, especially in online spaces.

The following regional and narrative summaries provide rich insight into specific challenges, narratives, patterns of radicalization, and violent extremist activities. These combined findings also contribute to a comprehensive understanding of regional and global P/CVE challenges.

Policy and programmatic recommendations are made in each regional report. At launch (23 May 2022), summary content on this microsite covers 2020-2021. Full regional reports with additional analysis, including country-level case studies, are available for 2020, while additional feature reports covering the second year of the pandemic (2021) will be published shortly.

The regions

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia was particularly proactive with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Although caseloads worsened the following year, pandemic-related health measures restricted regional mobility in general and violent extremist activity in particular. Pro-Daesh activity, especially, was substantially reduced until an uptick in late '21.

West Africa and the Sahel

The arrival of COVID-19 in West Africa in early 2020 meant that a region encased in complex extremist violence had to fight two deadly enemies with scarce resources. Violent extremist organizations across the region saw the pandemic as a prime opportunity and stepped up their violence, recruitment efforts, and state-building efforts as they spread misinformation about the pandemic.

East Africa

COVID-19 has claimed upwards of 250,000 lives across Africa. During the pandemic crisis, “violent extremists have been able to exploit deteriorating security, social, and economic circumstances to gain further support for their ideologies.” Insights from over 100 interviews across East Africa, including the Horn, illustrate the varied impact of COVID-19 on terrorism and violent extremism amid escalating attacks in the region.

The Balkans

Across the Balkans, COVID-19 pandemic circumstances and related weaponized conspiracies significantly impacted the nature and trends in violent extremist (VE) activities. The radical right, esoteric conspiratorial groups, and, to a lesser extent, Daesh-inspired and ideologically motivated actors capitalized on the pandemic to promote their ideologies.