The Reshaping of the Terrorist and Extremist Landscape in a Post Pandemic World

A major research program investigating the impact of COVID-19 on terrorist and extremist narratives.

West Africa and the Sahel

The arrival of COVID-19 in West Africa in early 2020 meant that a region encased in complex extremist violence had to fight two deadly enemies with scarce resources. Violent extremist organizations across the region saw the pandemic as a prime opportunity and stepped up their violence, recruitment efforts, and state-building efforts as they spread misinformation about the pandemic.

Choose which year of analysis to view via the slider below: 2021 or 2020.

Region Summary | Choose Year

In 2020, West African countries hurried to rally resources while watching the toll from the pandemic in early hotspots like Wuhan, China, and Italy, witnessing how even the most affluent and prepared countries of the world became overwhelmed. Priorities were re-drawn as governments scrambled to shore up their healthcare systems and deployed precious funding from fighting violent extremist organizations (VEOs). Militaries were put on high alert for potential enforcement of lockdowns, hospital transfers, and mass burials. VEOs and non-state armed groups (NSAGs) across the region saw the pandemic as a prime opportunity and stepped up their violence, recruitment efforts, and state-building efforts as they spread misinformation about COVID-19.

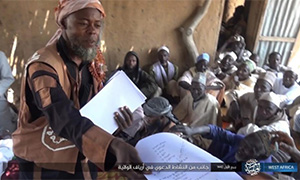

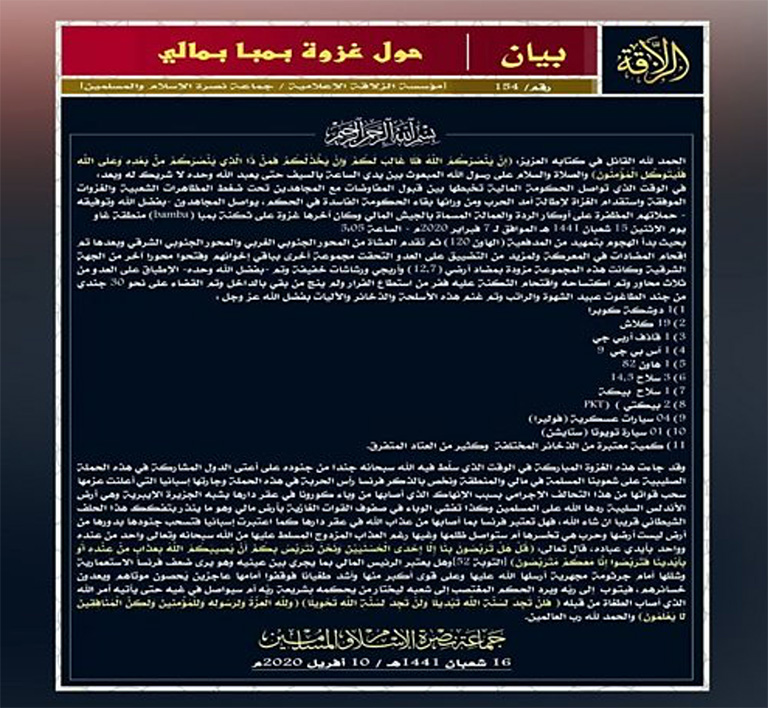

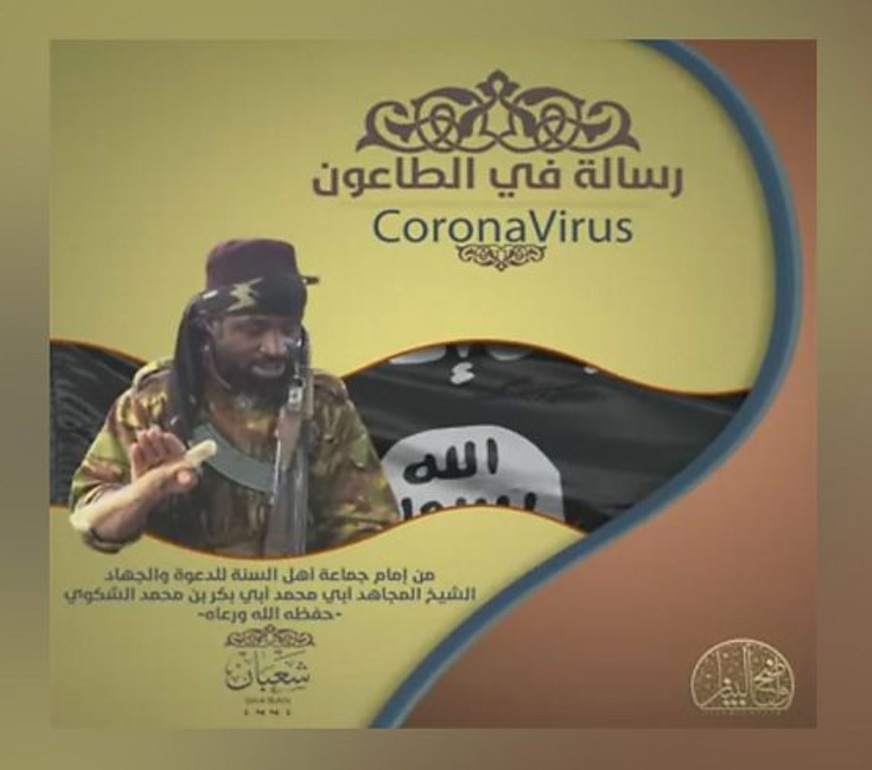

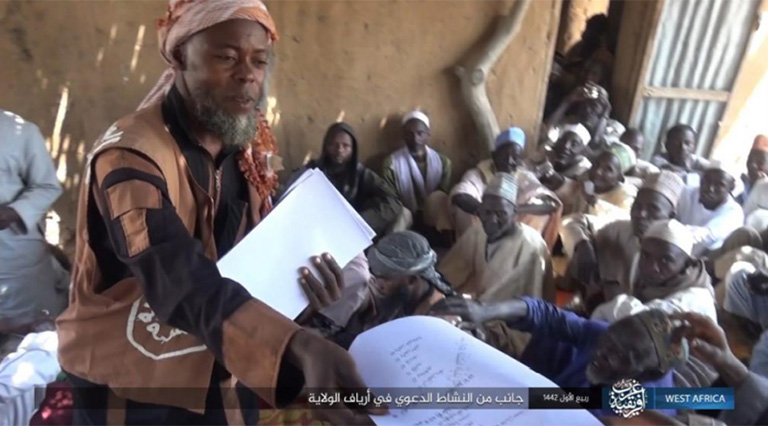

Examples of extremist narratives and propoganda in West Africa and the Sahel

Even though West Africa was – at least in 2020 – spared the worst human losses from COVID-19, the economic and social impacts were far-reaching and devastating. In addition to the thousands of deaths directly caused by the virus across the region, the strain it put on healthcare systems drained resources from patients with other conditions such as HIV, cancer, and sickle cell, thereby indirectly killing and affecting more people. Strict public health measures to control the pandemic led to the closure of schools, thereby disrupting education and arguably causing children to lose structured educational opportunities and, though not yet fully studied, potentially become more vulnerable to radicalization or recruitment.

Closures of shops and places of worship, restrictions of travel and social gatherings, layered with ongoing food insecurity, led to severe disruptions of economic, social, and religious activities. These rifts fueled protests and public unrest in several West African countries. In this operating environment, VEOs manipulated or capitalized on the above structural and societal challenges for their own ends.

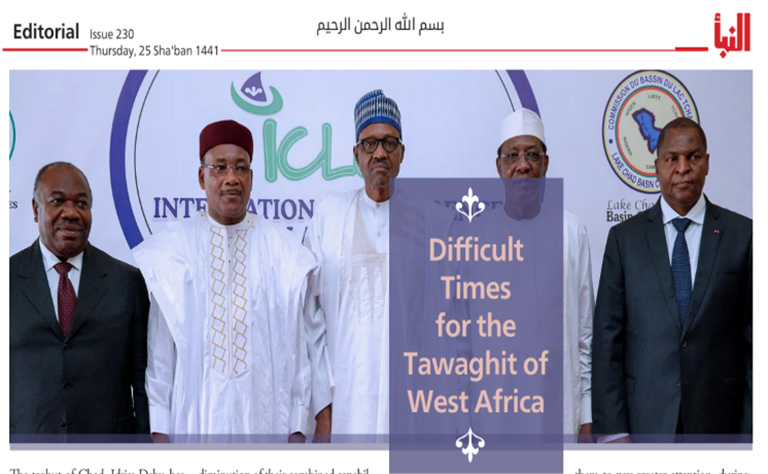

Cover of Issue 230 of the Daesh Al-Naba Magazines

2020 saw an upsurge of VEOs and NSAGs attacks, recruitment efforts and state-building activities by groups in territories where they wielded power across West Africa. A direct correlation between VEO attacks and COVID-19 is hard to show. However, the evidence is clear that the two pulled governments in opposite directions as VEOs worked to exploit COVID-19 ideologically, operationally, and strategically.

For instance, by creating and disseminating misinformation about COVID-19, VEOs sought to undermine public health measures and control the pandemic to accomplish their own goals.

NSAGs, generally less ideologically driven than VEOs, did not produce narratives similar to those of VEOs. However, COVID-19 allowed NSAGs to have more capacity to plan, train, and operate as governments focused on the pandemic and had reduced capacity to respond to their threats.

Ultimately, COVID-19 added another layer of complexity to an already dire situation in the Lake Chad Basin and central Sahel. The economic downturn caused by the pandemicnegatively impacted governments’ ability to confront VEOs, since domestic funds were redirected from counter-terrorism to health care, service provision, and efforts to boost employment.

Similarly, international donor priorities for preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE) programs were, understandably, constrained by COVID-19 assistance. Even with governments’ efforts to provide for their people, pandemic relief demands left openings for exploitation. Where VEOs found ungoverned spaces with compromised, contested, or weak government presence, they sought to increase their own appeal and demonstrate their own competence through service provision. As such, they attempted to not only undercut governmetns, but attempted to win the sympathies of underserved local populations.

Finally, the pandemic exacerbated poverty and unemployment, which, while far from the only variables, were among factors that facilitated recruitment to VEOs in West Africa in 2020.1

Recommendations:

- Transparent spending on public health, military capacities, and non-kinetic approaches should be a priority. The economic downturn created by COVID-19 risks derailing West African government efforts against VEOs. These countries need to delicately balance pandemic response with combating VEOs. This will require careful prioritization and allocation of resources.

- Given the rapid spread of dis- and misinformation campaigns online, it is essential to focus on digital resilience by creating and implementing digital literacy training programs. These should work with inoculation-based counter-narratives aimed to deconstruct conspiracy theories and misinformation campaigns while supporting communities with practical online and offline tools.

- By strengthening border security, West African counties can mitigate both COVID-19 and international terrorism. Effective border security can help reduce the cross spread of the virus and, at the same time, aid in restricting VEO cross-border activities.

- Governments need to credibly address and provide mechanisms to resolve grievances by minorities inside their countries. COVID-19 has exacerbated social rifts and the concerns underlying them, which are in turn weaponized by VEOs. Credible public dialogues to address long-standing grievances should be prioritized in P/CVE programming.

- Governments need to provide additional security and protection for healthcare workers. Frontline workers engaged in responding to COVID-19 and distributing vaccines around areas face tremendous risks where VEOs operate. This would help contribute to the successful containment of the pandemic in vulnerable regions.

- Governments and partners should continue and increase working with traditional and religious leaders to expand public-health messaging. Their efforts to distribute factual COVID-19 information while countering religious-based misinformation from VEOs is crucial. VEOs combine COVID-19 and religious-based misinformation: both themes dangerously exacerbate each other if unaddressed.

Footnotes

United Nations Development Programme, (2017). Journey to Extremism in Africa: Drivers, Incentives and the Tipping Points for Recruitment, http://journey-to-extremism.undp.org/content/downloads/UNDP-JourneyToExtremism-report-2017-english.pdf; Mercy Corps, (2016). Motivations and Empty Promises: Voices of Former Boko Haram Combatants and Nigerian Youth, https://www.mercycorps.org/research-resources/boko-haram-nigerian; Institute for Security Studies, (2016). Mali’s young ‘jihadists’: Fueled by faith or circumstance?, https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/policybrief89-eng-v3.pdf.

Unmasking Boko Haram, (2020). Boko Haram – Abubakar Shekau Audio Message on Coronavirus – April 15, 2020 [online video], Presenter Abubakar Shekau, Lake Chad Area, 2020.

Thomas Hale, Noam Angrist, Rafael Goldszmidt, Beatriz Kira, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips, Samuel Webster, Emily Cameron-Blake, Laura Hallas, Saptarshi Majumdar, and Helen Tatlow. (2021). “A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker).” Nature Human Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8, as used by Our World In Data; and, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), acleddata.com.

Visit SourceCOVID-19 data aggregated from Our World in Data (https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases) based on confirmed cases sourced from the COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science (https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19) and Engineering (CSSE)) at Johns Hopkins University; and, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED, acleddata.com).

Region Reports

For full analysis and recommendations, download the region reports for 2020 and 2021.