The Reshaping of the Terrorist and Extremist Landscape in a Post Pandemic World

A major research program investigating the impact of COVID-19 on terrorist and extremist narratives.

West Africa and the Sahel

The arrival of COVID-19 in West Africa in early 2020 meant that a region encased in complex extremist violence had to fight two deadly enemies with scarce resources. Violent extremist organizations across the region saw the pandemic as a prime opportunity and stepped up their violence, recruitment efforts, and state-building efforts as they spread misinformation about the pandemic.

Choose which year of analysis to view via the slider below: 2021 or 2020.

Region Summary | Choose Year

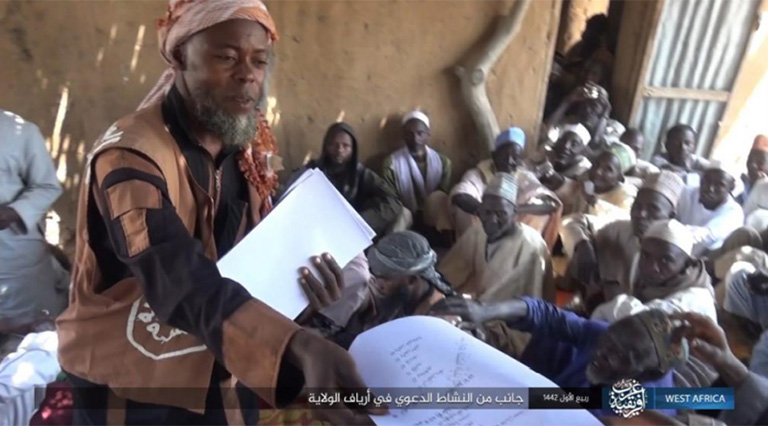

In the two years since the first reported case of COVID-19 in 2020, infections have spread significantly across West Africa. The pandemic has strained a region already heavily impacted by extremist violence, poverty, major education challenges, and climate unpredictability. Violent extremist organizations and non-state armed groups responded to the pandemic, exploiting the circumstances and increasing their appeal locally. 2020 saw extremists and other armed groups in the region react to COVID-19 in various ways. For example, violent extremist organizations and non-state armed groups changed their propaganda and in-person activities, such as preaching tours for recruitment and mobilization and recruitment tactics. The following year, in 2021, such actors were more aware of the potential impacts and opportunities presented by COVID-19. They capitalized on this understanding of the pandemic as a prime opportunity to scale up violence, drive recruitment, and work towards their ‘dreams’ to build so-called ‘states’ – a long-term vision to rule and reign over specific land, often cutting through internationally-recognized borders.

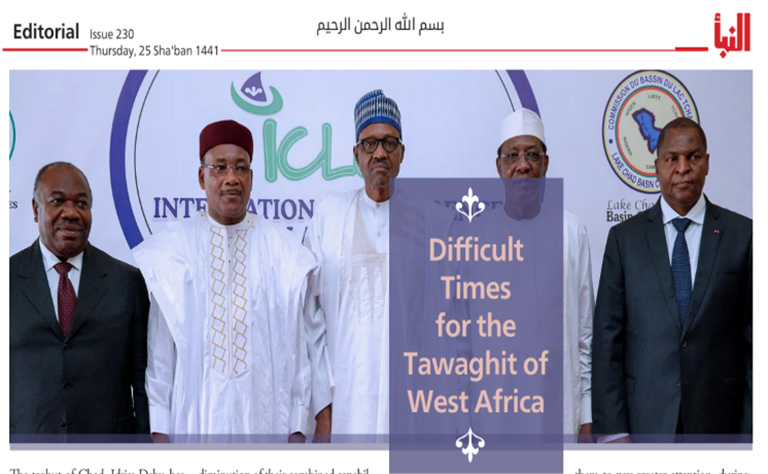

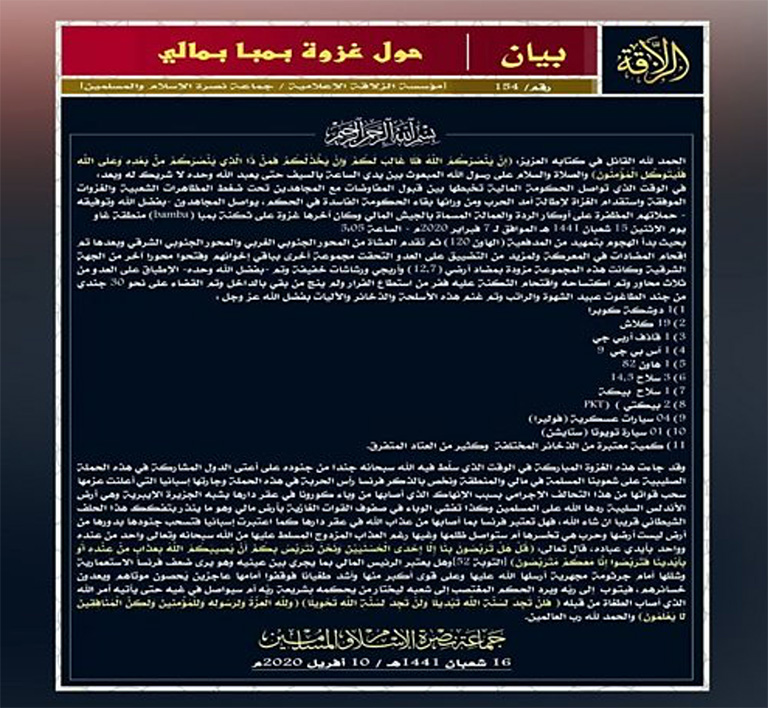

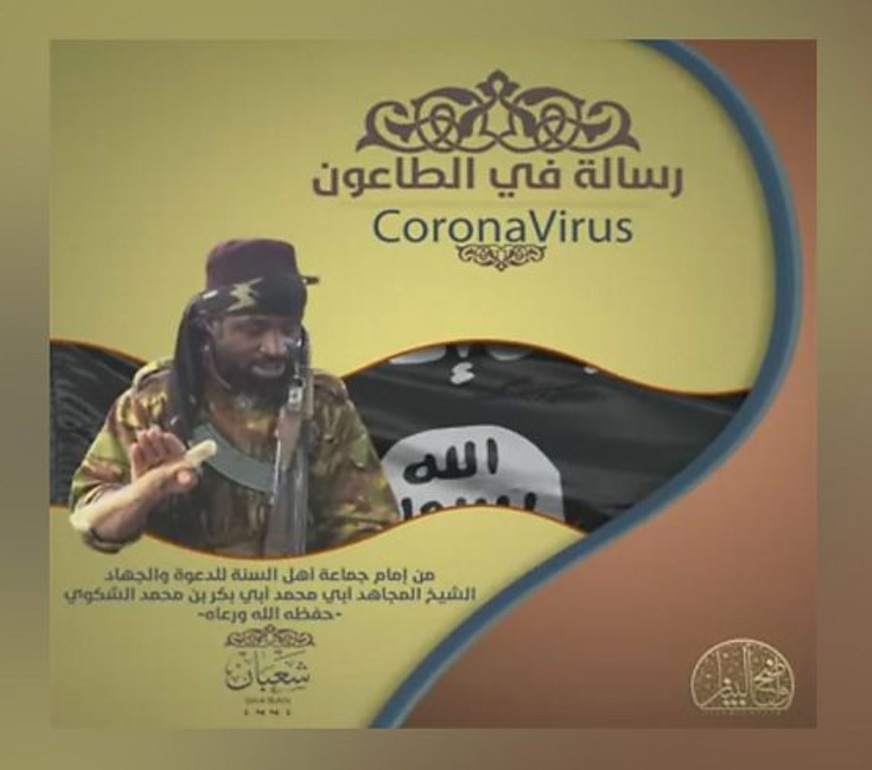

Examples of extremist narratives and propoganda in West Africa and the Sahel

In 2020 and 2021, the pandemic death tolls in the region were often under-reported due to inadequate data collection and a lack of testing equipment.1 Despite the global COVID-19 vaccine rollout, by December 2021, only 9% of the population across Africa was vaccinated – falling considerably short of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) target of 40% for every country.2 Between March 2021 and January 2022, Nigeria had administered the most vaccines per capita in West Africa at 9.93 doses per 100 people, followed by: Niger (7.35 per 100 people), Mali (6.96), Burkina Faso (6.02), Cameroon (3.86), and Chad (2.28).3

With the delayed rollout of vaccines in the region and negligible vaccines administered in remote areas where violent extremist groups generally operate, these groups did not focus their propaganda efforts on countering the vaccine rollout. However, propaganda from extremist groups about vaccines will likely follow when vaccine drives increase.

Throughout 2021, while COVID-related public health measures continued, compliance with these directives and restrictions has lessened.4 These measures led to the continued closure of shops, markets, places of worship, schools, and social gatherings and included domestic and international travel restrictions. Alongside continued food insecurity and conflict, these factors led to severe economic, social, and religious disruptions fueled protests and public unrest in several West African countries. A combination of these elements, while not immediately applicable to the impact of violent extremism on the region, forms a context in which violent extremist organizations operate.

A significant element that shaped 2021 in this region was the death of key leaders – both in extremist groups and in government leadership. Leaders of both Boko Haram factions, Jamaat Ahl al-Sunna lil-Dawa wal-Jihad (JAS) and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), died in the continuing conflict, as did the leader of Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS).5 The president of Chad, Idriss Déby, also died in May 2021.6 The death of these leaders led to infighting and a changing of tactics from both violent extremists and militaries. 2020 saw an upsurge of extremist attacks, recruitment efforts, and state-building activities such as regulating prices, adjudicating disputes, and levying taxes in territories where they exert power across West Africa. Meanwhile, 2021 brought a continued increase in activity from the groups as they learned to operate in new domestic and international dynamics affected by COVID-19 and changes in leadership. While a direct correlation between violent extremist attacks and COVID-19 is challenging to demonstrate, there are strong indications that extremist and terrorist actors attempted to exploit the pandemic while criticizing and undermining governmental responses to the pandemic.

In 2021, extremist groups across West Africa continued to create and disseminate propaganda to promote their ideological and general stances and activities. While in 2020, content disseminated related more closely to the pandemic and undermining public health measures, in 2021, there was considerably less content published that related to COVID-19. The content of propaganda was attenuated to activities of the groups, ideologies, visions, and attacks. The reduced COVID-19 content could be for several reasons: violent extremist organizations potentially perceive a reduced need to address the pandemic and because COVID-19 was less relevant with reduced public health measures. There was also an increased narrative focus on the social and political impacts of changes in leadership in countries.

Overall, the pandemic added another layer of complexity to the protracted humanitarian crisis in Central Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin area as violent extremist organizations stepped up their service provision efforts. The ongoing international economic downturn caused by the virus negatively impacted governments’ ability to confront violent extremist organizations throughout 2021 and their efforts at boosting employment.7 Additionally, international funding was redirected from various programs to addressing the COVID-19 pandemic.8 Despite governments’ efforts to provide for the needs of the people in the face of an unpredictable global pandemic, their responses were compromised by the extensive demands of supplies and tools needed to combat COVID-19. Violent extremist organizations exploited these circumstances and continued to increase their appeal through service provision of food, funding, or clothing for the poor.9 For example, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) claimed to have distributed food, clothes, and cash worth tens of thousands of United States dollars to poor people in the Lake Chad area. They have put considerable effort into attempting to win the sympathies of people living with less governance and where known drivers of radicalization are present.

Recommendations:

- 1. Prepare for an increase in propaganda against vaccines in West Africa. Violent extremist organizations in West Africa have not started public campaigns against COVID-19 vaccines, mainly because of the low number of vaccine doses administered in remote areas where these groups operate. There is a strong likelihood that violent extremist organizations will start disseminating anti-vaccination content once vaccines become more available. This will mainly be the case if pro-vaccine campaigns start and/or populations are mandated to be vaccinated. Governments in West Africa should anticipate this trend and address it by creating sustained educational pro-vaccination campaigns before such efforts begin, particularly as doses become available in areas affected by violent extremist organizations.

- Governments and international allies are encouraged to remain engaged on multiple fronts to present a united, common approach to responding to violent extremist organizations. In particular, international donors and local governments should provide support to address localized community causes of radicalization to violence. The rule of law, human rights affirmed law enforcement action, and harmonized approaches between local and international actors should also be prioritized.

- As the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic continue to devastate governments and communities, violent extremist organizations are increasing service provision in rural areas to win the loyalty and support of local communities. This trend may increase in the coming years during the potential struggles to repair the economic damage of COVID-19. To counter the latest violent extremist organizations’ tactics, governments and international organizations should increase humanitarian assistance to affected communities and build more sustainable solutions while addressing shortages of necessities to foster peace.

Footnotes

World Health Organization, (2021), Six in seven COVID-19 infections go undetected in Africa.

Visit SourcePeter Mwai, (2021), Covid-19 vaccinations: African nations miss WHO target, BBC News

Visit SourceWorld Health Organization, (2022), WHO Coronavirus. (COVID-19) Dashboard, (accessed January 25, 2022).

Visit SourceStanley Azuakola, (2021), West Africa Tackles COVID-19: Contrasting Regional Approaches to Combating the Pandemic, Global Policy

Visit SourceBulama Bukarti, (2021), This Looks Like The Beginning Of The End Of Boko Haram – We Should Accelerate It, Daily Trust

Visit SourceDeclan Walsh, (2021), Idriss Déby Dies at 68; Poor Herder’s Son Became Chad’s Longtime Autocrat, The New York Times

Visit SourceOxfam, (2021), The West Africa Inequality Crisis: Fighting Austerity and the Pandemic

Visit SourceEuropean Council, (2021), COVID-19: the EU’s response to the economic fallout

Visit SourceSahara Reporters (2021), 825 Packets Of Food Worth N3.4million, 353 Bundles Of Clothes Were Distributed To The Poor During Ramadan, Says Boko Haram

Visit Source

Region Reports

For full analysis and recommendations, download the region reports for 2020 and 2021.