The Reshaping of the Terrorist and Extremist Landscape in a Post Pandemic World

A major research program investigating the impact of COVID-19 on terrorist and extremist narratives.

The Balkans

Across the Balkans, COVID-19 pandemic circumstances and related weaponized conspiracies significantly impacted the nature and trends in violent extremist (VE) activities. The radical right, esoteric conspiratorial groups, and, to a lesser extent, Daesh-inspired and ideologically motivated actors capitalized on the pandemic to promote their ideologies.

Choose which year of analysis to view via the slider below: 2021 or 2020.

Region Summary | Choose Year

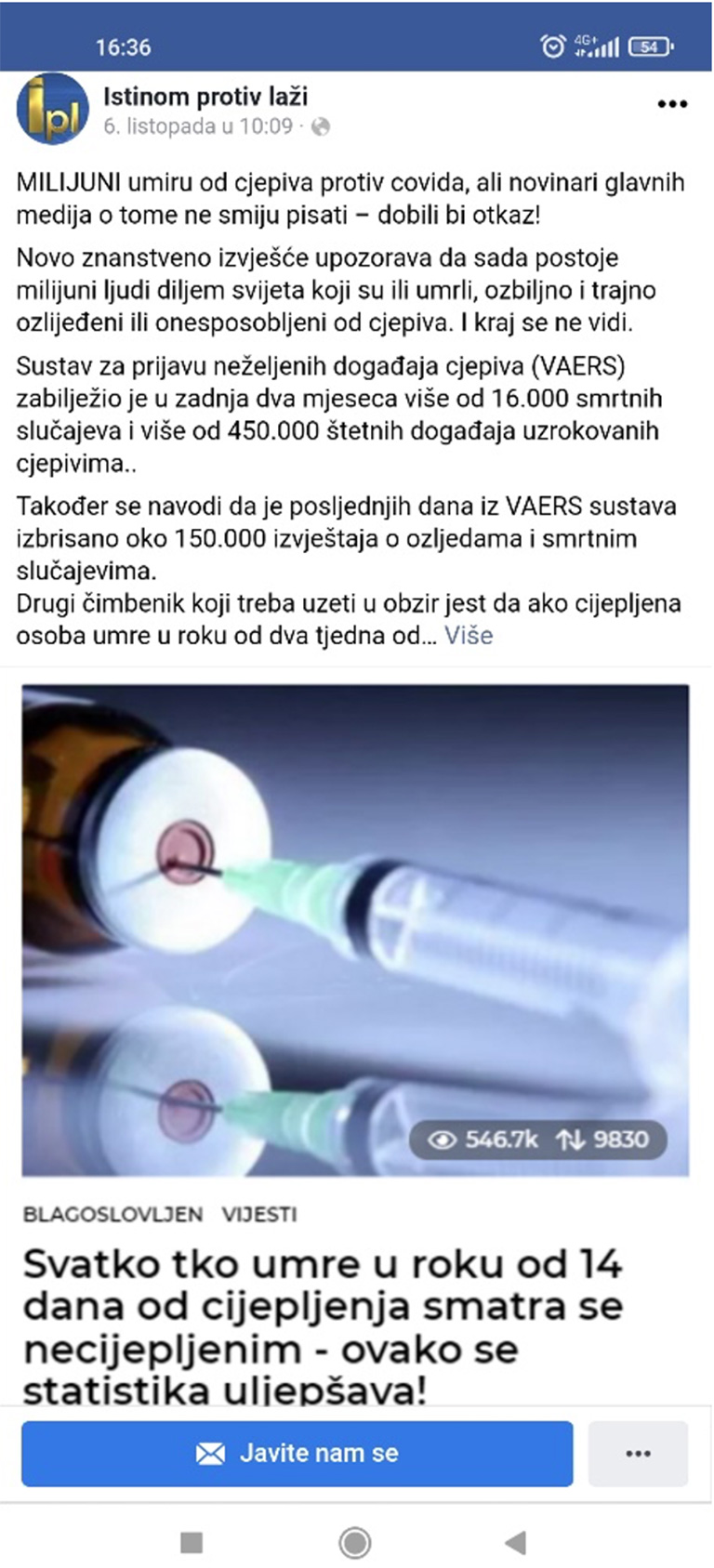

By disseminating COVID-19-related disinformation and conspiracies in their propaganda, extremist actors have muddled truths surrounding the health crisis in their attempts to radicalize and recruit new followers. Nonetheless, despite the evidence of high-mobilization levels online and offline, terrorist incidents remained rare. Exceptions mainly included individual attacks, arrests, and foiled plots. A potentially ideologically motivated 2020 shooting in Zagreb, the Republic of Croatia,1 and a separate, larger plot in the Republic of North Macedonia involving an 11-member cell – with one member reportedly having fought for Daesh in the Syrian Arab Republic – were the most notable incidents2.

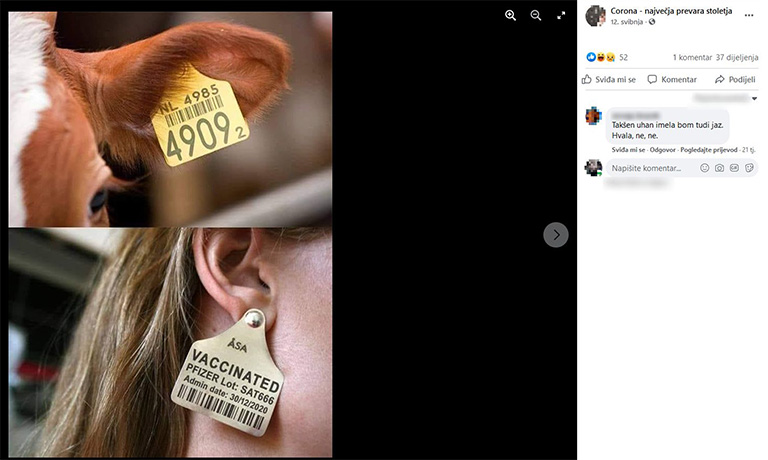

Examples of extremist narratives and propoganda in the Balkans

The Balkan region has witnessed other types of extremist activities in 2020, notably political demonstrations involving a wide range of different conspiracy theorists and extremist actors. In some circumstances, extremists leveraged popular political demonstrations, creating an environment where extremist ideologies intersected with ideas across the political spectrum. This has resulted in extremist narratives around COVID-19 that include Daesh-inspired, ultra-nationalist and radical right groups and actors. This report, therefore, identifies broader trends in narratives that span all of these groups.

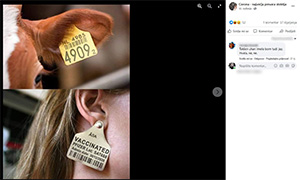

Post on the Facebook Page, “Corona – Največja prevara stoletja” (“Corona – The greatest deception of the century”). Source: Facebook (redacted).

Most notably, the pandemic has bolstered the radical right and conspiracy theorist actors in the Balkans more than other ideologically motivated extremist actors. This might be related to the downward trend of distinct ideologically inspired groups and individuals, particularly after the demise of Daesh in Syria and the Republic of Iraq and the globally rising trend of radical right extremism.

The repatriation, prosecution, rehabilitation, and reintegration efforts of Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTF) and returnees from Daesh-occupied territories continued, especially in the Western Balkan countries. Within this ideological spectrum, VE activities, terrorism, and new cases of radicalization and recruitment are rare, albeit it is noteworthy that a few arrests were made in 2020.3

The radical right, ultra-nationalist, and conspiracy theorist groups have rapidly expanded over the past few years, and their extremist activities often linked to COVID-19 conspiracies and narratives, continued to grow in 2020. At times, these organizations and individuals appear to intersect and overlap with mainstream social and political discussions in the region. Such groups and actors have therefore been very successful in instrumentalizing the pandemic circumstances to increase their visibility and reach through online spaces and social media platforms; this has been particularly effective due to an uptick in online activity in the region as a result of strict curfew enforcements leading citizens to spend more time browsing the Internet.4 Consequently, an increase in online radicalization and recruitment during 2020 has led to several serious incidents on the ground.

Romanian QAnon demonstrators. Source: Buletin.de Bucuresti, “QAnon, o mișcare din SUA care a convins mii de români că Donald Trump e salvatorul lumii. Își trimit copiii cu măști false la școală și se pregătesc de distrugerea ocultei mondiale satanice buletin.de,” (accessed 15 October 2021).

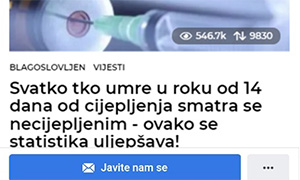

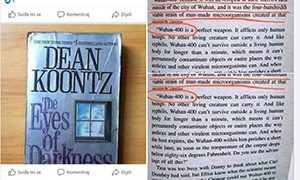

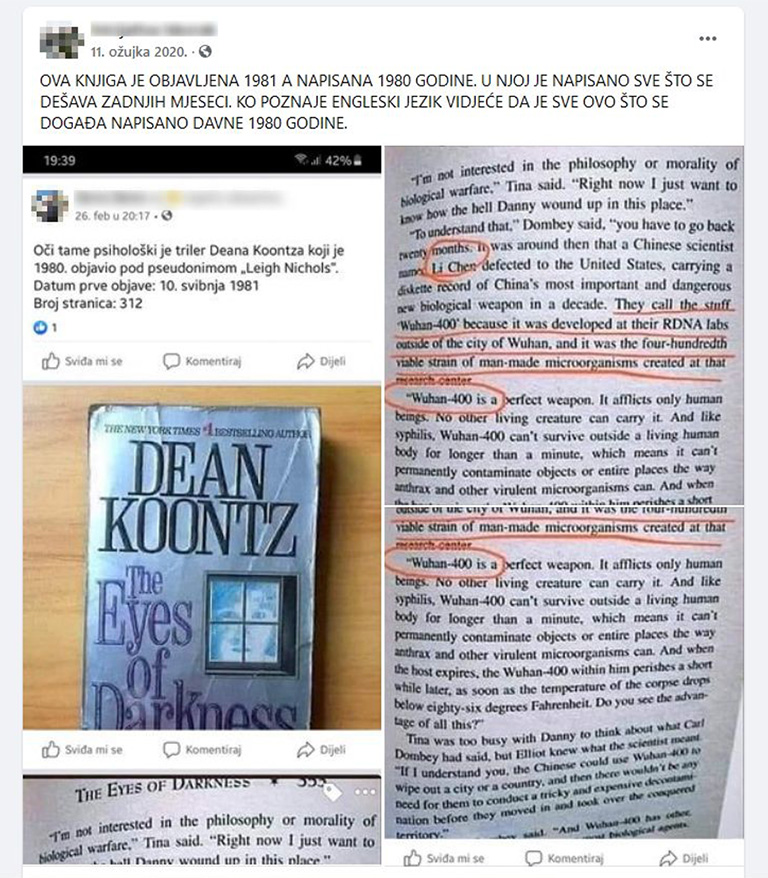

View sourceDisinformation and conspiracy theory campaigns have permeated the region, many of which originate from adherents of the QAnon offshoot known as “QAnon Balkan”.5 Such stories are picked up in the uncritical, or perhaps deliberate, dissemination of disinformation and fake news in mainstream media. Radicalized and VE actors have seemingly not decamped to new alternative social media. Disinformation campaigns often run on mainstream platforms. Attempts to counter fake news, when made by governments, may run afoul of a lack of confidence and trust in governments and politicians. Simultaneously, an aversion to COVID-19 restrictions created a breeding ground for conspiracy theories and anti-establishment propaganda that was often synchronized with ideas that existed before the spread of the virus.6

While extremist and violent narratives vary from country to country in their interpretation of the pandemic, there are collectively shared trends among different groups and individuals, distilled into five core elements below:

- A robust online presence of QAnon groups and followers who disseminate misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories on social media, mainly Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, Viber, and Telegram. The most common false theories include shared themes, including collective depictions of the detrimental nature of 5G technology, face masks, and vaccination (the latter often tied to Bill Gates); shared ideas about a secret society controlling the world and the virus, and governments’ attempts to accentuate dictatorship via lockdown measures; and theories about the location and purpose of the emergence of the virus;7

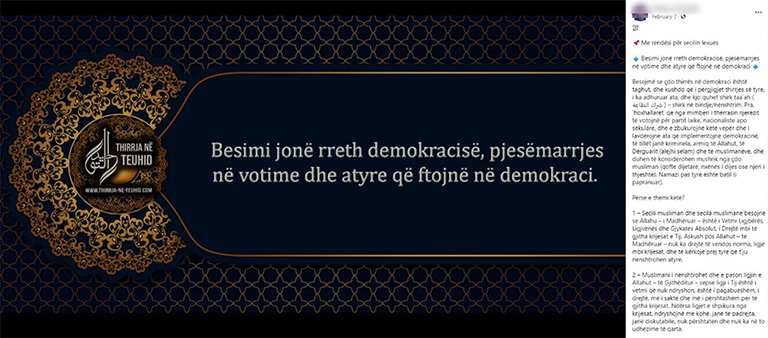

- The propagation of conspiracies by religious and esoteric actors and leaders, including orthodox clerics and followers of various categories of alternative spiritual practices in the Republic of Serbia and the Republic of Moldova;8

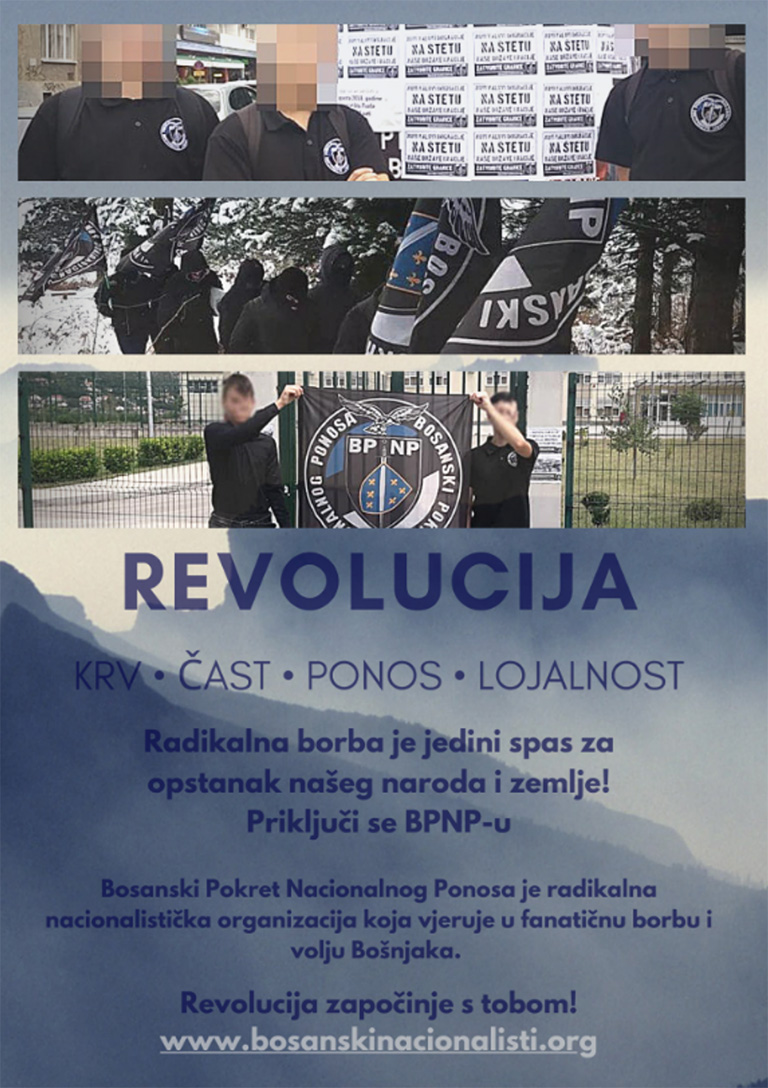

- Notable ideological overlaps between the broader radical right, including ultra- nationalist adherents, QAnon followers, esoteric groups, and lone actor narratives that are at times related to conspiracy theories;

- The active circulation of religious interpretations of the pandemic being a divine punishment in the Republic of Albania and the Republic of Kosovo;9 and,

- • A rise in radical right in form of ultra-nationalist VE narratives and incidents in the Republic of Slovenia, the Republic of Bulgaria, Serbia, Croatia, and the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina with historically deep roots linked to previous regional conflicts.

Policy recommendations

Based on the research and insights gathered in the development of this report focusing on the year 2020, several recommendations are provided below for governments and policymakers in the region:

- With the evident widespread of disinformation and misinformation campaigns, conspiracy theories, and VE narratives online – including through mainstream media outlets – governments are advised to:

- Collaborate with technology and social media companies through partnering with credible organizations such as the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) and Tech Against Terrorism (TaT), but also independently with other high- tech companies. Such partnerships can support the collaborative development of legislation between governments and social media companies dealing with terrorist narratives. These partnerships can also lead to developing streamlined communication mechanisms between governments and the tech sector on how to monitor and remove harmful content online.

- Fund training for journalists to increase their awareness, knowledge, and practical skills to accurately and unbiasedly report on issues related to radicalization, VE, terrorism, or inter-ethnic and inter-religious regional clashes. Partnerships with international organizations that focus on countering violent extremism (CVE) should be further developed; and,

- Launch public awareness campaigns to inform and educate citizens about the dangers of the rampant spread of disinformation and misinformation online inside a more comprehensive program of digital literacy education.

- Increased regional collaboration and government funding are needed to investigate and prevent the alarming rise of the radical right, ultra-nationalist, and conspiracy theory movements, groups and actors, and related trends. Informed and evidence- based policymaking, and CVE National Action Plans (NAPs), especially in countries where implementation is nonexistent or slow, are required to prevent the spread of this form of VE and terrorism.

- There is a need to intensify efforts on collaboration between the government and official religious clerics and moderates within the countries and involve them in the CVE efforts. Although ideologically motivated extremist groups and individuals, mainly those inspired by organizations such as Daesh and Al-Qaeda, were less active in 2020 – narratives by adherents of such ideologies still produced and spread harmful content online during the pandemic. Among other activities, this effort can involve training religious leaders and active community members on identifying and handling radicalization that can lead to VE.

Footnotes

Note: Information as to the motivations of Danijel Bezuk, the perpetrator of the Zagreb shooting, remains unclear. Although the State Attorney's Office of the Republic of Croatia evaluated the attack as terrorism, criminal charges were rejected due to the shooter’s death.Vecernji, “Proslo je godinu dana od napada Danijela Bezuka na Vladu: ‘to je bio terorizam,’” Vecernji.Hr, 12 October 2021

Visit SourceEUROPOL, 'European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report, Publications Office of the European Union', EUROPOL, Luxembourg, 2021, p. 65, (accessed 23 September 2021).

Visit SourceGCERF, “Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Returning Foreign Terrorist Fighters (RFTFs) and Their Families in the Western Balkans,” GCERF (accessed 20 January 2022).

Visit SourceMatteo Mastracci, “Online Intimidation: Controlling the Narrative in the Balkans,” Balkan Insight, 16 December 2021 (access 20 January 2022).

Visit SourceJoe Mulhall and Safya Khan-Ruf, eds., “State of Hate: Far-Right Extremism in Europe 2021,” Hope not Hate, p. 41. Charitable Trust and the Amadeu Antonio Stiftung

Visit SourceFlorian Bieber et al, “The Suspicious Virus: Conspiracies and COVID19 in the Balkans”, BiEPAG (accessed 20 January 2022).

Visit SourceIbid. and; Buletin, “QAnon, o mișcare din SUA care a convins mii de români că Donald Trump e salvatorul lumii. Își trimit copiii cu măști false la școală și se pregătesc de distrugerea ocultei mondiale satanice,” Buletin de Bucuresti, 21 October 2020 (accessed 20 January 2022).

Visit SourceDW, “Korona ne poznaje Boga,” DW, 11 November 2020, https://www.dw.com/sr/korona-ne-poznaje-boga/a-55691345 and Europa Liberă, ‘Mitropolia Ortodoxă a Moldovei, supusă Moscovei, împrăștie teorii ale conspirației, Europa Liberă Romaniă, 20 May 2020 (accessed 20 January 2022).

Visit SourceArmand Ali, Facebook

Thomas Hale, Noam Angrist, Rafael Goldszmidt, Beatriz Kira, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips, Samuel Webster, Emily Cameron-Blake, Laura Hallas, Saptarshi Majumdar, and Helen Tatlow. (2021). “A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker).” Nature Human Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8, as used by Our World In Data; and, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), acleddata.com.

Visit SourceCOVID-19 data aggregated from Our World in Data (https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases) based on confirmed cases sourced from the COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science (https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19) and Engineering (CSSE)) at Johns Hopkins University; and, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED, acleddata.com).

Region reports

For full analysis and recommendations, download the region reports for 2020 and 2021.