The Use of Psychoeducational Training to Prevent Radicalization Leading to Violent Extremism

by David Ludescher

Our first article on a specific project of the STRIVE Global program brings us to the Western Balkans, more specifically to Serbia.

In this post we will present the project “Youth for Change: Building the resilience of Serbian youth through engagement, leadership and development of their cognitive and social-emotional skills” from the Psychosocial Innovation Network (PIN). It started its implementation in mid-2019 and came to an end in October 2020. First, we will present the organization, second, we will present the background, and third, its implementation, and its outcome and impact.

Background

In 2017, the Serbian government adopted the “National Strategy for Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism and Terrorism for the Period 2017-2021”[1], which is based on a comprehensive and multi-faceted approach. Violent extremism first gathered attention throughout Serbia with the rise of the Islamic State and the recruitment of Islamic fundamentalists and extremists from all over the world to fight in the conflict in Syria. According to police estimates, several dozens of people, mostly from the Sandžak region but also from other parts of Serbia, have joined the IS or other terrorist organizations such as the Al-Nusra-Front in recent years. A poll by the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia conducted among the youth in Sandžak showed that one fifth of the questioned youth believes that defending their own religion through violence is justified, and one out of ten supports going abroad to defend Islam[2]. Not only religious extremism constitutes a problem in Serbia, but also far-right extremism. Since the violent break-up of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in the 1990s and after the 2000s and the beginning of Serbian democratic transition, right-wing movements have been present in the country, spread hate speech towards vulnerable groups and minorities and are involved in violent incidents.

In the past, Serbian authorities have responded to the issue of extremism in the country in a predominantly non-systemic and securitized approach, not appropriately exploring alternative prevention strategies. Moreover, there is a trend towards apathy, alienation, and indifference towards politics among the youth, with youth unemployment being exceptionally high at over 30%. Young people furthermore have a desire to prove themselves as valuable members of their communities. If they do not feel like they are part of their community, and if they question their identity, there is an increased risk for them to join extremist groups, who with their clearly defined structures can give them a sense of belonging and identity. Some of the more vulnerable communities in the country are to be found in the Sandžak region. This is the case as the Sandžak region has a strong Muslim community while Serbia is a predominantly Christian Orthodox country. They mostly identify themselves as Bosniaks, and thus constitute an ethnic minority. There are often tensions between the different ethnic groups, especially during times of political turmoil and election cycles. Finally, the refugee crisis in Europe has also played an important role in the country during the last years. After the EU closed its borders for refugees traveling on the Balkan route, Serbia turned from a transit country into a country where refugees ended up staying for years and seeking asylum. Numerous young refugees have consequently enrolled in the Serbian education system.

Youth for Change

The project “Youth for Change: Building the resilience of Serbian youth through engagement, leadership and development of their cognitive and social-emotional skills”, aimed at addressing both local and refugee youth’s needs. The action addressed the areas of education, acquisition of knowledge, and community engagement, in order to counter youth radicalization. One of the main goals of the project was to improve youth’s cognitive, social, and emotional well-being and resilience, and ensure that they have a safe space for sharing ideas and the challenges they are facing, facilitate adaptive coping strategies, support them in exploring their individual and group identity, as well as question social pressures to which they are sometimes exposed to from their peers, families, and communities. The project further aimed to strengthen peer support and informed decision-making among youth, facilitate their social integration, and support their civic engagement and empower them to play an active role in their communities. Finally, the project strived to promote inclusive peace and reconciliation, encourage understanding, tolerance, and respect, and reduce radicalization among Serbian youth. The rationale of the action was thus that if young people increase their cognitive and social-emotional skills and competencies such as inter-cultural sensitivity, along with their well-being and sense of belongingness to their communities, their resilience to violent extremism will be enhanced. The project’s approach followed some of the key principles of the Abu Dhabi Memorandum on good practices for education and countering violent extremism, such as using a multisectoral approach, relying on empirical evidence as a basis for the development of the curriculum, emphasizing the concepts of problem-solving, providing multiple perspectives on the topic, and involving youth in the development and planning of educational activities related to countering violent extremism. The program constituted a valuable asset for the Serbian National Strategy for the Prevention and Countering of Terrorism and addressed several of its objectives, such as gaining a better understanding of the issue of radicalization in the country, creating an environment discouraging the recruitment and participation of youth in terrorist groups, raising awareness on the dangers of social media and the spread of hate speech, and creating alternative narratives to terrorist propaganda.

First steps and baseline report

The cities of Novi Pazar and Sjenica, two of the most populated towns in the Sandžak region, as well as the capital Belgrade were defined as target cities. These cities have been chosen as the Sandžak region was the region from where most people joined the IS, and as youth outside of Belgrade typically reports more traditional patterns of thought, long-established value systems and customs, and a more patriarchal, homophobic, and violent behavior[3]. Additionally, the city of Sjenica as the city is home to an asylum center accommodating unaccompanied refugee minors, and the program could positively influence the intercultural sensitivity in the city. To get the implementation going, as a first step four Memoranda of Understanding with the four schools that participated in the project. A cooperation with the different schools is essential for such a project as they are already familiar with their environment, have a good knowledge of the challenges the youth are facing, and the school staff can profit from the training in preventing radicalization among youth and continue applying these skills after the end of the project. Additionally, the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development approved the implementation of the project in the schools and the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Belgrade assured its participation in the development of the project manuals.

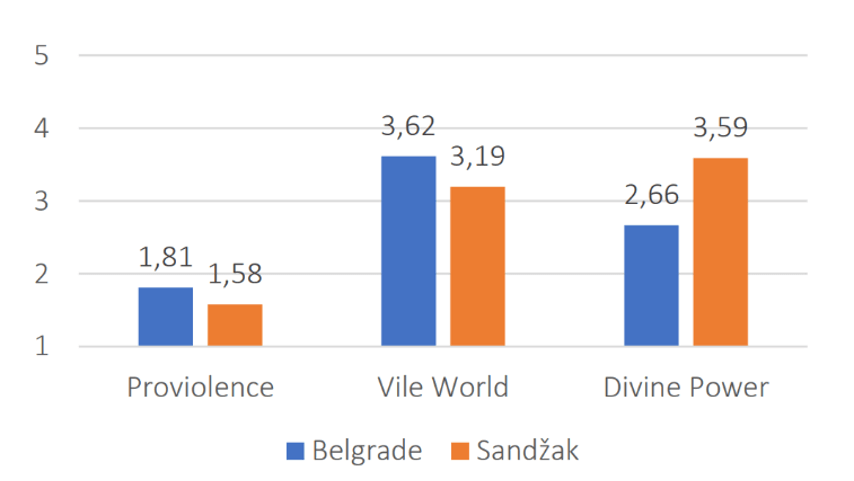

To gather data and analyze the attitudes and values of the students prior to the participation in the psychoeducational workshops, a baseline study was developed that can be found here[4]. 288 students filled out the questionnaire before the training in order to provide data to assess their cognitive and social-emotional skills and competencies and their sense of belongingness to their communities. The same questionnaire was then filled out at the end of the workshops in order to evaluate the impact of the project. The baseline study provided several results. First, it was shown that both the students from Belgrade and from the Sandžak region predominantly interact with their own ethnic group. In Belgrade, low levels of acceptance were specifically found for Albanians and the Roma population, while in the Sandžak region lower acceptance was mostly found for Croatians and the Roma population. In this study, radicalization and violent extremism proneness were conceptualized through the three-dimensional Militant Extremist Mindset (MEM) scale, which assesses acceptance, justification, and advocacy of the use of violence in certain circumstances, beliefs in divine power such as heaven and god, or the role of martyrdom and afterlife pleasures, and the belief of the present-day world as vile and miserable and heading for destruction. The three components that are part of the Militant Extremist Mindset have different psychological and contextual roots. Pro-violence tendencies can be mostly explained by psychological factors such as group inequality and social isolation and loneliness. The vile world component on the other side is mostly explained by contextual factors and can usually be seen in students coming from dysfunctional families and having been exposed to a hostile school environment. Finally, the divine power component seems to be best predicted by one’s religiosity, but also by right-wing authoritarian tendencies. In the baseline study, both regions showed a limited acceptance of violence, with the youth in Belgrade having a slightly larger acceptance of the use of violence. Both regions, but especially the youth in Belgrade, showed above-average levels of the perception of the world as a vile and miserable place. Finally, students from the Sandžak region showed a moderately strong belief in divine power, mostly linked to their religiosity.

Psychoeducational workshops

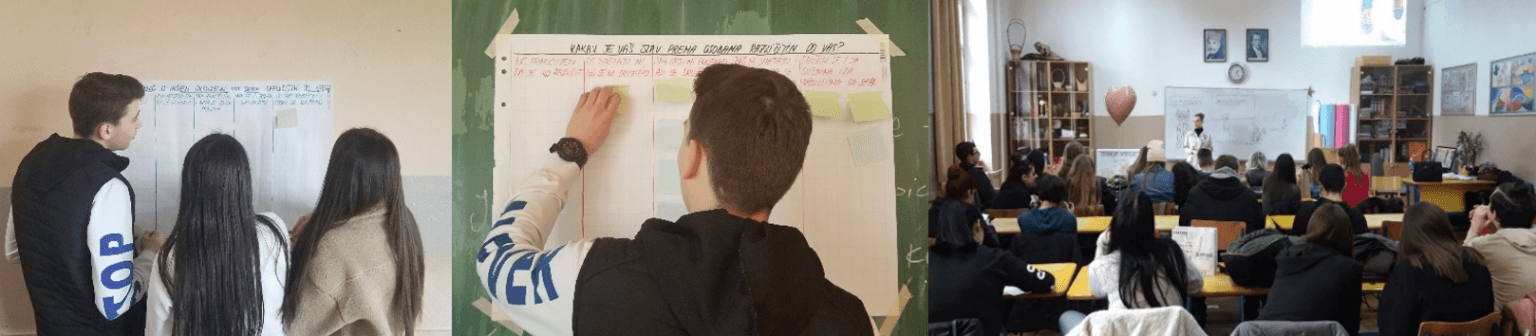

It is very important to discuss the discrimination that surrounds us”

Workshop participantAs one of the main activities of the project, a psychoeducational program tailored to the context of Serbia was developed. The main goal of the workshops was to strengthen cognitive and social-emotional skills relevant for the students’ overall development and well-being and for preventing and countering violent extremism. The program included 10 modules on topics like identity, self-confidence, problem-solving, prejudice, discrimination, cultural differences, and others. The full workshop program called Building Youth Resilience to Violent Extremism (BYRVE) Program can be found here[5].

Over the course of five months, 251 students from the four different high schools participated in the workshops. The students selected for the program were aged between 15 and 19, the reason being that numerous studies have shown that young people of this age group constitute the social group most vulnerable to violent extremism. Their natural impulsivity and willingness to take greater risks, among others, may also be contributing factors to their propensity to join groups or movements that may espouse violence. At the same time, these factors influence young people’s search for their own identity, a purpose, recognition, and belonging. Therefore, it was of great importance to this program to offer young people a safe space for sharing their ideas, facilitate adaptive coping strategies, support them in exploring their individual and group identity, as well as questioning social pressures to which they are from times to times exposed to. In the evaluation of the program the students showed that they had greatly enjoyed the program, found it useful and interesting, and had developed a healthy relationship with the experts providing the training, stating that they would like to continue with such a training in the next school year.

End-line report

After the end of the workshops, an end-line report was concluded to measure the overall impact of the action. The sample group of the Belgrade region showed a significant decrease in one of the three MEM factors, being the pro-violence mindset, in respect to the control group. Furthermore, there was a trend-level decrease in right-wing authoritarian mindsets recorded. Regarding the vile world and the divine power factors, no significant changes were recorded in either of the regions. This did not come as a surprise, as these factors are deeply rooted inside people and predominantly determined by one’s early socialization and childhood and youth experiences and cannot be quickly changed through a short psychoeducational program. Furthermore, the divine power component is rooted in one’s religious belief and should not be considered as a predictor of extremist beliefs per se, but simply as a possible amplifier in people with already high pro-violent tendencies. When it comes to other ethnic groups, a trend-level acceptance increase was recorded in both regions. In Belgrade, the acceptance of Bosniaks, Croats and Albanians increased, while the acceptance of Roma remained low in both regions. The lack of improvement in the factors of isolation and loneliness can at least partially be explained by the pandemic that arose during the project, with the students being isolated at home. This also led to a lack of opportunities to engage with new people and practice the newly adopted social skills and attitudes and thus partially explains the low improvement in the intercultural sensitivity scale. For anyone who is interested to know more about the collected data and the statistical analysis conducted through the Militant Extremist Mindset scale (MEM), PIN has written a journal article called “Contextual and Psychological Predictors of Militant Extremist Mindset in Youth” which discusses the findings of the baseline study and reveals a complex interplay of contextual and psychological drivers in the prediction of different aspects and risk factors of radicalization leading to violent extremism. The results further highlight the importance of linking radicalization to the social context, past aversive experiences, and psychological factors such as loneliness and isolation.

Youth leadership program

For the youth leadership program, 18 students who had attended the workshops were elected by their peers through a participatory election process. Involving them in the process of a democratic election was an opportunity for them to experience and understand democratic values as well as taking an active role in the program. For this youth leadership program, an additional educational training program was developed. As with the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic it was not possible to hold it in person, the training was adapted to be an online training. The goal of this training was for them to become youth leaders in their communities. Through the training they discovered their own potential by developing interpersonal and leadership skills, increasing their self-confidence, and acquiring the motivation and ability to bring about positive change to their communities. A strong focus was put on ways to recognize and prevent radicalization leading to violent extremism, in order to use these skills to prevent radicalization among their peers and provide positive alternative narratives. The training program contains nine modules on topics like public speaking, leadership skills, or understanding and countering violent extremism and can be found here[6]. As seen through a pre- and post-test on the topics discussed, knowledge of the relevant topics increased significantly. Initially, teachers and school staff, as well as family members, peers and other members of the local communities were planned to be targeted through several events and thematic meetings autonomously organized by the youth leaders. The goal of these events was to raise awareness on the problem of radicalization leading to violent extremism. Unfortunately, due to the spread of COVID-19 in the country, no events could be organized by the youth leaders in their local communities. As an alternative, they came up with the idea of filming a video on the project, which was shared online to ensure the visibility of the project and reach the target groups. In this video, several youth leaders from the three different cities explain what they have learned throughout the project and what has most impressed them. The video also portrays the training personnel from PIN as well as the school staff, and how they experienced the workshops and youth leadership program.

Final presentation

With a final meeting concluding the project, community members and representatives from the local authorities, local NGOs, and national violent extremism experts were targeted. As, due to the pandemic, no live event with a larger audience was possible, an online meeting was held and broadcasted from the Media Center in Belgrade. Under the title How far are we from a society that accepts: Presenting research results, PIN’s project manager and assistant presented the project activities as well as the results from the base- and end-line studies. During that broadcast, PIN also presented the results from a study on Attitudes toward refugees and migrants, which was conducted by PIN in cooperation with the Open Society Foundation (OSF) Serbia. The main topics of this study were discussing the attitudes in Serbia toward different groups, such as different ethnic groups and refugees and migrants, and explaining the protective and risk factors that can lead to radicalization leading to violent extremism, as well as showing possible ways of prevention through psychoeducational programs. The broadcast was followed by several hundred people and a video can be found here[8]. An article on the project was further published in the independent Serbian newspaper Danas[9]. Finally, a publication “Youth for Change: Building the Resilience of Serbian Youth” summarizing the project and its main findings has been sent to all involved stakeholders, as well as to local and national authorities, which can be accessed here[10].

Conclusion

I already use these skills in everyday life – understanding and generosity are the keys to living together"

Workshop participantThe students greatly enjoyed the workshops and the youth leadership program and would have wished for them to continue. In their feedbacks they said that they found it very interesting to hear the different experiences of their classmates about stereotypes and discrimination. They also claimed that the workshops helped them take another perspective they did not have before and learn something completely new. All in all, through the implementation of the psychoeducation workshops, a decrease in the pro-violent mindset and the acceptance of right-wing authoritarianism was recorded. Furthermore, the acceptance of other ethnic groups increased in both regions and an increase of cognitive, social-emotional and leadership skills was achieved. The lack of significant changes in the other aspects of the MEM scale can be attributed to several factors. Psychological traits are deeply rooted in one’s personality, and their change requires more time and a more individual-oriented approach. Nevertheless, the project has been a full success and opens the doors for future interventions based on the approach used by PIN. The four documents developed by PIN throughout the implementation of the project have also been transferred to the Ministry of Education, which could use the training program in other schools in the future. Furthermore, the psychoeducational program and the online youth leadership training program were jointly published in a bilingual handbook for facilitators. Further information and impressions on the project can be found on PIN’s website and their social media channels.

Thank you very much for tuning in and we hope you liked the read. Next month we will portray a project from the journalism strand, namely from the Novi Sad School of Journalism in Serbia.

References

[1] https://rm.coe.int/serbian-national-strategy-for-the-prevention-and-countering-of-terrori/168088ae0b

[2] https://www.helsinki.org.rs/doc/files35.pdf

[7] https://youtu.be/GYh-4GF9SKE

[8] https://youtu.be/NvLYAg_B_3w

[10] https://psychosocialinnovation.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Publication_PIN-_STRIVE_ENG.pdf

About the Psychosocial Innovation Network

PIN is a Serbian non-governmental, non-political and non-profit organization which was founded in 2015 with the aim of achieving a diverse set of goals in the field of psychological practice and protection of mental health. PIN engages in the design, implementation and evaluation of different psychoeducational interventions and community-based support programs for youth and individuals from vulnerable and marginalized groups, that aim to protect and enhance their emotional, psychological, and social well-being. PIN further strives to establish and promote multisectoral, evidence-based, comprehensive, and efficient models of psychosocial support which engages beneficiaries, service providers, local communities, and policy makers in the creation of systemic and sustainable solutions for mental health protection and improvement.

Psychosocial characteristics in that sense describe the influences of social factors on an individual’s behavior and health. PIN’s activities are divided into four different program areas which are: (1) psychological interventions and counselling, (2) psychosocial support including educational programs, (3) research, and (4) advocacy work. Activities implemented by PIN include, among others: developing and applying diverse psychological interventions, promoting and strengthening empirically-based psychological practices, raising awareness of various social and psychological challenges, particularly related to vulnerable and marginalized groups, designing and conducting capacity building training and seminars for beneficiaries, fellow organizations and policy makers, as well as cooperating with national and international practitioners, institutions, and stakeholders. PIN has in the past completed over 25 projects in cooperation with a diverse set of international organizations.

About STRIVE Global In Focus

The STRIVE Global: In Focus series will present a series of articles presenting the overarching STRIVE Global program, as well as insights and outcomes from its projects. The STRIVE Global program aims at building the capacity of state and non-state actors to effectively challenge radicalization and recruitment to terrorism while continuing to respect human rights and international law. Throughout its implementation, the program has supported 36 different civil society organizations in the Western Balkans, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, the MENA region, and Turkey.

In this series, we will present one of these organizations and its respective project each month. The series serves as a contribution to the conversation around diverse CVE solutions and pushes forward the quest for more research and innovation in the field. The authors of the articles are the STRIVE Global team and the opinions expressed in these articles are their own and not representative of Hedayah.