The Reshaping of the Terrorist and Extremist Landscape in a Post Pandemic World

A major research program investigating the impact of COVID-19 on terrorist and extremist narratives.

Restrictions as Repression

Societal divisions and polarization around the world intensified during the pandemic. Government measures introduced to reduce the spread of the pandemic – including lockdowns, face masks, and limits on public gatherings – faced heavy criticism and public backlash. VEOs in the regions studied continually expanded their narratives to exploit these sentiments and rally against restrictions. Often their framing sought to warrant a broader anti-government stance or to advance views that specific religious groups were being unjustly targeted. In their view, restrictions in the aims of public health became repression.

About this narrative

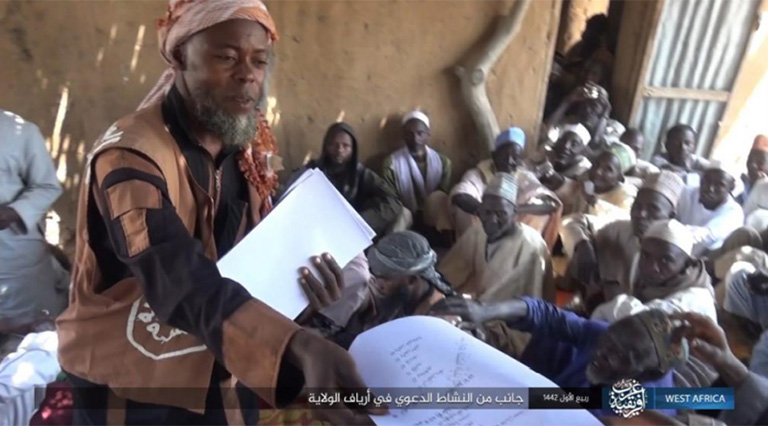

In West Africa, VEOs used public health measures introduced in response to the pandemic as a narrative exploit to persuade their audiences. In April 2020, the former leader of Boko Haram, Abubakar Shekau, described public health measures as an intentional ploy by non-Muslims and hypocrites to prevent Muslims from practicing their faith.1 During the 2020 Eid festivals (both of which took place during national lockdowns), extremist groups operating across West Africa released videos and photos of congregational observance – some of which mocked and denigrated Muslims who observed public health measures during the festivities.2 Daesh-affiliated VEOs circulated promotional documents (including propaganda such as photos of dead soldiers) with ideologically-based guidance to ignore COVID-19 restrictions.3 Interestingly, extremist groups in the Lake Chad region and the Sahel did not keep pace in 2021 with the volume of COVID-19 misinformation they disseminated in 2020. This may be a result of different factors, including: (a) having produced a significant amount of misinformation on the virus the previous year, VEOs might have thought that they had sufficiently dealt with the topic; or, (b) as most public health measures had been lifted or wholly ignored in practice, COVID-19 itself had become less relevant to its audiences than the previous year; and/or, (c) the previous campaigns may simply not have been very effective.3

Examples of the Restrictions as Repression narrative

In East Africa, VEO narratives often framed Muslims as victims of pandemic restrictions. Abubakar Shekau declared that social and distancing measures introduced by the Nigerian government constituted a war against observant followers of Islam.4 Meanwhile, a Tanzanian religious leader reiterated that lockdowns aimed to deny Muslims the right to pray communally. In Somalia, Al–Shabaab denounced hypocrisy from governments that allowed shopping malls and markets to continue trading while mosques were closed in 2020.5 The following year, the same group urged Muslims not to be used as “guinea pigs in the race to develop a potent vaccine” for COVID-19. Al-Shabaab seemingly spread these types of harmful narratives to gain support from the public and advance recruitment efforts.

In the Balkans, as pandemic restrictions impacted religious and other social freedoms, extremist groups sensed an opportunity. Violent extremist organizations, particularly associated with the radical right, promoted weaponized mis- and disinformation about COVID-19, called for the rejection of governmental anti-COVID measures, and encouraged active participation in demonstrations where peaceful protesters met mingled with violent extremist groups. For example, banners used at 2021 anti-government protests in Croatia called for greater participation by sympathizers of radical right political parties. Political figures present at these protests were exclusively members of right-wing parties, while the use of Ustasha (an historical fascist party) salutes and marches by linked military-styled battalions took place during the year.6 In Albania, the spiritual leader Armand Ali used religious gathering restrictions to incite discontent about religious freedoms being taken away on his Facebook page. Comments on the page claimed that the government was infringing on religious freedom by limiting prayer gatherings under the pretext of COVID-19 restrictions.7 In other countries in the Balkans, radical right actors and groups spread misinformation drawing on repressive restriction narratives. In Montenegro, for example, radical right groups used social media tag-lines like “STOP Covid Tyranny” and “STOP Tyranny on Children.”8 Bunt Crna Gora, founded in 2020 in response to Montenegro’s new law on religious freedom, similarly expanded its political activism in 2021 by disseminating COVID-19 disinformation and propaganda focused on a loss of freedoms in the country.

As elsewhere in the Balkans, radical right actors across Bulgaria attempted to discredit public health measures through narratives denying the dangers posed by COVID-19. The Croatian group, “Rights and Freedom Initiative,” called for people to “take off the mask, turn off the TV, live life to the fullest” and declared “better the grave than to be a slave.”9 In May 2020, a demonstration in Romania brought together the media channel Sputnik, conspiracy theorists, and the right-wing AUR (Alliance for the Unification of the Romanians). During the demonstration, speakers contended that COVID-19 did not exist and the government was dictatorial, criminal, and trying to restrict fundamental freedoms.10 The activities and rhetoric of the radical right extremists became more extreme towards the end of 2021. For instance, during a demonstration supposed to commemorate the revolution of 22 December 1989, AUR sympathizers attempted to storm the Parliament building.10

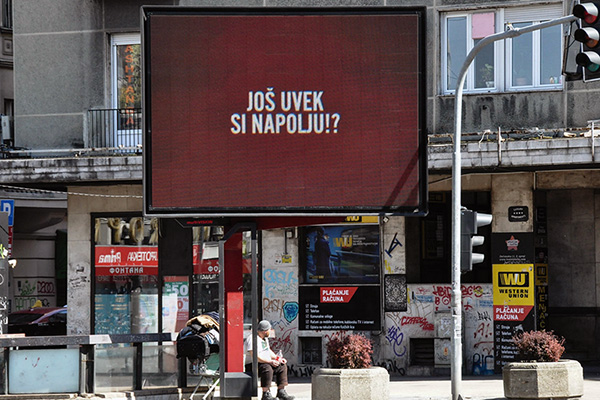

Anti-government narratives in Serbia were also given credence by perceived heavy-handed police tactics at demonstrations against COVID-19 during 2020.11 Subsequent Facebook groups and initiatives in Serbia (such as ‘I live for Serbia’) popped up and appealed to audiences with radical right views. Several of the most active groups in this space included “People’s Patrol,” “Stop Censorship,” and “I live for Serbia” which actively participated in anti-government protests and were visibly engaged online. They promoted anti-immigration, anti-vaccine, and anti-government narratives while arguing against the EU and the succession of Kosovo. This rejection of any ‘territorial division’ of Kosovo is mated with pandemic-specific twists accusing the government of using the lockdown as a cover to secretly settle migrants in Serbia.

In Moldova and Romania, there was a strong religious influence in radical right and COVID-19 conspiratorial narratives, with religious symbology and clergy leaders often being present. A number of priests belonging to the Metropolitan Church of Moldova organized an anti-vaccination demonstration in August 2021. Demonstrators claimed they opposed compulsory vaccination and demanded liberty; some also claimed the vaccine was a biological weapon to reduce the world population through microchips, or that certain religious psalms protect against the pandemic.12 Individual religious icons and clergy were also present at anti-pandemic public health measure protests, despite the official position of the Romanian Orthodox church supporting government measures.13

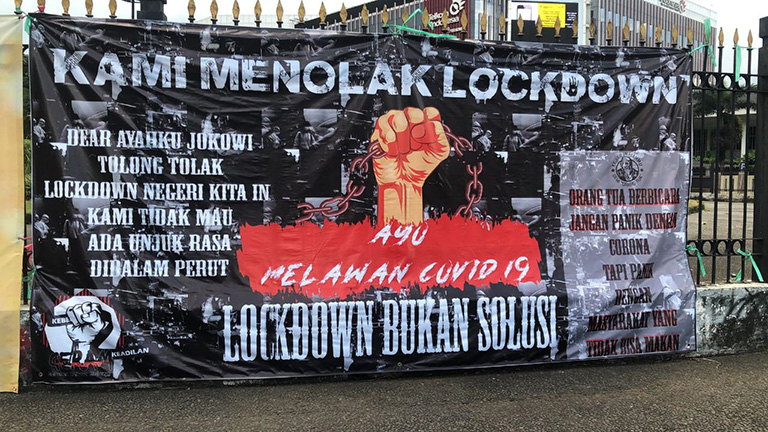

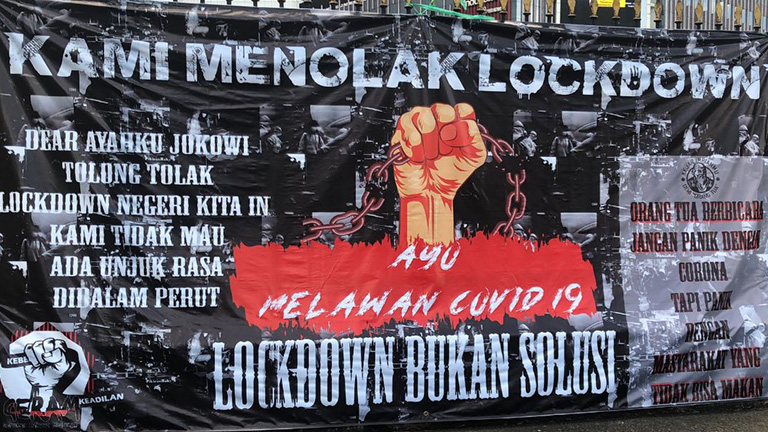

In Southeast Asia, narratives about repressive restrictions became more prominent toward the end of 2020 as COVID-19 cases multiplied across the region and governments imposed lockdowns. VEOs changed their narratives to reflect vehement opposition to these new restrictions – particularly when they began interfering with religious and political activities. In 2021, after leading attacks on COVID-19 public health measures and circulating disinformation on the origins of the virus during the year prior, a broad array of Indonesian actors including Hizb-ut Tahrir Indonesia, pro-Daesh supporters, and others intensified anti-government online disinformation campaigns. Proliferating Telegram groups exhibited the most extreme anti-government rhetoric. These groups adopted some of the militant imagery and language of Daesh, using posters and videos to call on supporters, albeit in vague terms, to fight the Indonesian government.

Footnotes

Unmasking Boko Haram, (2020). Boko Haram – Abubakar Shekau Audio Message on Coronavirus – April 15, 2020 [online video], Presenter Abubakar Shekau, Lake Chad Area, 2020 (accessed 12 October 2021). Translation from Hausa to English by authors.

Boko Haram, “This is our Eid Video”, (accessed 1 June 2020).

J. Zenn, “Unmasking Boko Haram: Exploring Global Jihad in Nigeria,” (multimedia supplement).

J. Campbell, “Boko Haram's Shekau Labels Anti-COVID-19 Measures an Attack on Islam in Nigeria,” Council on Foreign Relations [website] (accessed 18 October 2021)

Visit SourceR. Haula, COVID -19 Pandemic and Al Shabab’s Operations, Nairobi, Kenya, BRAVE Insight, 2020; M. Oduor, ‘Al-Shabaab issues warning against AstraZeneca vaccine’, Africanews (31 March 2021), accessed 20 October 2021.

P. Stošić, 'Covid-prosvjedi dali su ekstremnoj desnici priliku života', Index.hr, 3 December 2021, (accessed 15 January 2022);

Visit SourceArmand Ali, Facebook (accessed 23 September 2021).

’Rights and Freedom Initiative’, Facebook (accessed 15 July 2021).

D. Vulcan, 'Piața Victoriei, protest care contestă existența cazurilor de coronavirus. Se cere pedepsirea celor care au instituit starea de urgență', Europa Liberă Romania, 15 May 2020, (accessed 15 October 2021).

E. Isaila‚La AUR, nu demonstraţiile împotriva măștii și vaccinului sunt problema, ci extremismul și violența', Spotmedia.ro, 22 December 2021, (accessed 5 January 2022)

Visit Source“Protests continue in Serbia against pandemic curbs,” Andalou Agency, 2020.

Visit SourceDigi24, 'Preoți ai bisericii subordonate Rusiei au organizat un protest anti-vaccinare la Chișinău', Digi24, 3 August 2021, (accessed 25 October 2021); Radio Europa Libera, ' Protest al preoților și enoriașilor în centrul Chișinăului: „Nu trebuie să fim vaccinați cu sila. Dați-ne libertate!”', Facebook, 3 August 2021

Visit SourceDigi24, 'Purtătorul de cuvânt al Patriarhiei s-a vaccinat împotriva Covid-19. Bănescu: Pledez pentru informarea credincioșilor de către preoți', 5 April 2021, Digi24, (accessed 28 October 2021)

Visit Source